The pandemic and its disparate effects on students and families have prompted many educators to commit to the idea of leaving inequitable practices of the past behind. In the Quincy, Washington, school district, where I work, the disruption of the past two and half years has fueled specific changes in how we engage with families and students.

Before the pandemic hit, family engagement in our district meant working with individual families to support their children, encouraging attendance at school events, and fundraising. Most decisions about the school's programs and vision for family engagement were driven by hard "data." But in the periods of remote and part-time, in-person learning, student growth became directly tied to how well educators supported families to create conditions for learning at home (Sperling Center for Research and Innovation, 2021). For the first time, families became the leaders of classroom management and students' go-to resources for academic feedback and technical support. For the first time, family priorities led learning systems.

In my district, this shift felt like a silver lining in the midst of a tough period. We learned how to listen better and to more deeply understand students' experiences of learning from home. Families' priorities drove our decisions, which helped us strengthen relationships between our community and our schools in one of the most challenging times in history.

Learning to Listen with Empathy

Like most districts, mine closed in the spring of 2020 without a cohesive plan for digital teaching and learning. As a digital education coach, I was hired to work with teams across schools to adopt a common digital learning platform, implement 1-1 devices for students, and envision a remote model for teaching and learning. My colleagues and I had no idea how to build these systems or ease the burden on students, families, and staff. We needed to start by listening—very carefully.

That's where using empathy interviews came in. Empathy interviews, a listening practice used by organizations like Stanford d.School and The Learning Accelerator, involve targeted, one-on-one conversations with a small sample of people to learn from their lived experiences (Bamford & Curry-Jahn, 2020). I had heard about empathy interviews in a virtual training at the beginning of the pandemic and shared the idea with district leaders, who saw the value in using them to gain a more holistic picture of our community's needs. They allowed us to collect stories that ultimately drove district decisions—such as choosing a learning management system, deciding how meals would be distributed, and creating health and safety protocols for the return to school. Our current process, which I coordinate and monitor, is a combination of recommendations from other groups and our own practices that we've continued to refine along the way.

Through it all, we learned that empathetic listening starts with the questions we choose to ask long before we sit down and talk. We learned that it continues after a voice grows quiet—in shifting our mindset to understand stories as data and truly letting this data lead our next steps. We learned that empathetic listening drives us to honor families' trust by getting back to them in a timely way and communicating about the actions their feedback informed.

The empathy interview process starts with careful planning and questions such as, To whom do we need to listen most closely?, How can we ask questions that will draw out the depth in their stories?, and How can we create a trusting environment for open communication? This intentionality takes a great deal of time and resources, but the rewards are worth the effort. I have seen this process return the rich data we hoped for, lead to better decisions, and transform relationships between our families and schools.

Consideration #1: What do you want to learn and why?

The power of empathy interviews lies in the depth and color of the stories shared (Bamford et al., 2020). To draw out those rich stories, you need well-crafted prompts. Consider the subtle shift between these two options: "What do you like about reading?" versus "Tell me about a time you felt proud of yourself as a reader." The first may prompt a specific text or a mode of reading that the student prefers. The second will drive the interviewee to their memory, calling up a moment in time attached to a specific emotion. These storytelling moments help those using the data to step into the shoes of others and to empathize with their lived experience.

As you plan, select four to six questions that allow interviewees to express both positive and challenging experiences within the topic. Stay focused on the big picture, whether that is recovery from the pandemic or student experiences with learning to read. Broad, general questions give interviewees the opportunity to think beyond their specific memories at school to their community and home life. This can provide even more context to their responses, as well as a wealth of new ideas that educators may not otherwise consider (Nelsestuen & Smith, 2020).

Some effective stems could be:

Tell me about a time that you have felt happy or proud during …

Can you tell me a story to help me understand more about …

What are your best or worst experiences with …

If you had a magic wish and could change one thing about ___, what would it be?

These types of prompts are effective because they elicit stories of the interviewee's lived experience at specific moments in time. They can also be adapted to use with families, students, and even staff to gather comparable data.

Consideration #2: Whose voice do you need to hear?

Empathy interviews are conducted, by design, with a very small sample of the overall population. Too much qualitative data can quickly become unmanageable. So once educators identify what they want to focus on in the interviews, they must stop to consider whose voices to prioritize. In Quincy, this prioritization was driven by a race and equity policy that the district was developing around the same time. Guided by this new policy, which established a vision for collaborative decision making, especially with families and students who have historically been left out of these processes, our team knew we must prioritize the voices of those who were most marginalized within the school system.

Disaggregating typical data metrics such as grades, discipline, and attendance helped us identify patterns across various student groups. We noticed that male students who qualified for both special education and our school's transitional bilingual program struggled disproportionately on every metric. This was true at every grade, across up to five years of data. We desperately needed to hear their stories and to commit to letting their priorities lead us.

So, when conducting an interview cycle related to reopening schools after the pandemic, our team decided to speak with K–12 male, multilingual students in special education and their families. The families were mainly interviewed over the phone due to COVID-19, but questions were similar for both groups. The interviews revealed that these students and families desperately wanted to return to a school where both they and their families had strong relationships with peers and staff and where discipline consequences would be consistent and fair. Family members asked us to continue with digital communication and access to learning at home. They asked for higher expectations and more authentic learning experiences. Finally, they asked us to continue thinking flexibly about learning environments and to stop focusing so much on seat time.

We used this feedback to prioritize the use of our emergency relief funds under the federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund. We hired additional mental health counselors and recommitted to positive behavior interventions. We continued 1:1 device programs and provided hotspots for students learning at home.

Some district leaders questioned our decision to base spending on the responses of such a narrow cross section of students. But our superintendent stayed focused on what we'd seen in the data and on our conviction that schools couldn't be better unless they got better for the boys our actions had been harming the most.

Empathy interviews are a powerful tool, not only because of the rich data they provide, but because of the trust and empathy that they build along the way.

Consideration #3: Who will conduct the interview?

The quality of the interview hinges on the level of trust between each interviewer and the person they are interviewing, so one of the most important considerations is carefully selecting those who will lead the conversations. The interview will be most meaningful if the interviewer speaks the same language and has an established relationship with the person they are interviewing.

The interviewer uses their judgment to decide how much elaboration to push for and to monitor how the interviewee is feeling and responding to each question. Through this process, the empathy interview isn't just about gathering data—it also strengthens the relationship between typically marginalized families and the school (Ishimaru, 2019).

Leaders in our district decided that family empathy interviews would be best conducted by parent liaisons at each school. These staff members live in the community and speak the language of the families they serve. They are the families' first point of contact when they call the school or stop by the office. The liaisons also worked with the principal to identify families to interview.

In one recent interview cycle, one of the parent liaisons sought me out to recap a conversation she had just had with a parent who has not previously engaged with the school. The parent emphasized her support for the school's reading curriculum and passionately shared about the work the family was doing at home to make sure the student would become fully biliterate in English and their native Spanish. Not only did the school and the district now better understand the parent's hopes and dreams for her child, but the experience added a layer of positivity into the relationship between the liaison and parent, which will support the child throughout school.

Families' priorities drove our decisions, which helped us strengthen relationships between our community and our schools in one of the most challenging times in history.

Consideration #4: How will you conduct the interview?

Each time the district used empathy interviews, my colleagues and I learned more and refined our protocol. We began to provide specific training to the family liaison interviewers. This gave them time to review the content, ask questions, and develop a common understanding about why we were asking for feedback in this way. The more clearly we learned to articulate the interview goals and process, the more buy-in our administrators and interviewers had. At the beginning of every interview, we share some combination of the following questions and statements:

Our school/district is getting ready to …

I'd like to ask you some questions to understand more about …

A committee will read the responses that you tell me, but your name will be private.

If you don't feel comfortable answering some of the questions, that is ok. If you don't want me to ask you these questions, I can ask someone else.

Is it OK if I ask you some questions now?

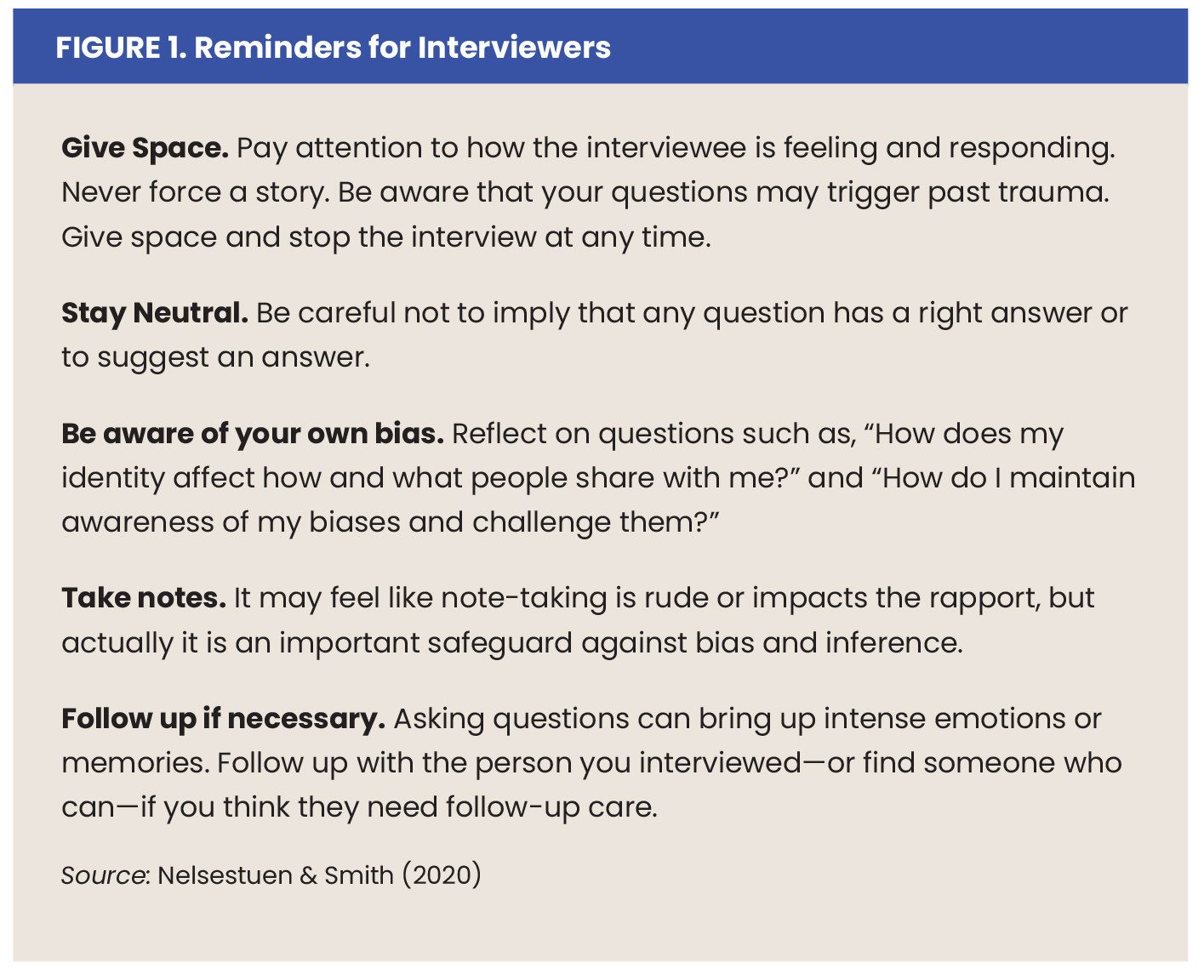

See Figure 1 for more important reminders that drive our interview protocol.

Consideration #5: What will you do with the data?

The real work of listening with empathy begins after the interview ends. Honoring those who share their stories happens through what you do with the stories and how you communicate the value of what you learned to those you talked with. During the pandemic, these feedback loops were necessarily quick and clear in our district. We used family input to build a remote and hybrid learning model essentially from the ground up. We asked what they wanted, they told us, we figured out how to make it happen within our constraints, and then we rolled out the next steps, reminding them that their ideas informed the design.

Now that we're in person, that work takes more intentional planning—but it is worthwhile. One of the biggest interview cycles we engaged in last year was part of a K–5 curriculum adoption for English Language Arts. A consistent theme in interviews with students and parents was their desire for schools to improve our writing program—better instruction, more opportunity, deeper practice. As one parent told us,

My child has shared with us that he feels proud when he writes and is given the opportunity to read what he writes. Last year, when he was in 3rd grade, he got home from school full of joy because he was brave enough to read out loud in front of the class.

Throughout the selection process, as well as scheduling and professional development decisions to prepare for implementation, I have continued to hear district leaders and teachers reminding each other of that priority and where it came from. As we roll out the implementation with students this fall, we will intentionally point back to their feedback as the inspiration for the steps we have taken.

As I reflect on the past two years, I now see how the lessons we've learned from empathy interviews have taught us to look at all data differently—what it is, how we gather it, and which data is most valuable. For the past year, we've used these lessons as we prioritized the mission, vision, and goals in our new strategic plan—grounded in qualitative data from family and student voice. Now we're going back to families to ask them what they would consider progress toward those goals to help us develop the metrics we'll use to measure the plan's success. The hope is that more schools will be able to harness direct family voices and involvement to guide positive change. Empathy interviews are a powerful tool toward this goal, not only because of the rich data they provide, but because of the trust and empathy that they build along the way.

Reflect and Discuss

➛How do you currently involve student and family voices in your school processes?

➛What are some topics that would be most helpful to focus on for your own empathy interviews? Who would you prioritize speaking to first?

➛What challenges do you anticipate to implementing an interview process?