What does it mean to disrupt inequity?

I can name a few historical acts that surely qualify—Rosa Parks claiming a seat in the front of the bus, for one. Risking arrest and violence against herself, she spurred the question, Why is it fair for persons of one color to receive an ordinary service like front seats and those of another color to be sent to the back of the bus? Her action reverberated to other inequities: unequal access to drinking fountains, lunch counters, decent housing, quality education.

When I hear about actions taking place today, however, it is harder to tell what constitutes an effective act of inequity disruption. Results are not yet in, and controversies in social media swirl.

Will the affluent black athletes' refusals to salute the American flag as a protest against racial injustice make a difference? High school students are emulating their actions on local football fields, but my old-fashioned view makes me wonder whether it would it be better for the pros to donate a portion of their not insignificant salaries to schools that are disrupting inequity. And perhaps, instead of a silent protest, the students should gather together with their classmates and teachers to discuss inequities at school out loud?

On the other hand, what does it accomplish for a mostly white group of churchgoers, of whom I was one, to participate in their first "conversation about race" when we can't really decide what the first step is? Is it to talk and listen to the congregation of black churchgoers a few miles away? Or is it something else entirely, having to do with changing our own minds and hearts?

Two-hundred years of slavery, 100 more of inadequate "reconstruction" efforts, and another 50 years fighting an unfinished civil rights battle are in our history. Thus, many acts seem trivial in the face of what needs to be done.

Then a coworker tells me of another act of recent "disruption." A teacher in an urban Boston school, after visiting her colleague's school across town, got mad at the differences she saw back home. First, she was struck by the beautiful books in her friend's classroom. "I need those books for my kids," she thought. But what was really the last straw was the clean and shiny desks. "We don't even have enough desks!" Encouraged through TeachPlus, a group that inspires teachers to find their voice, she made her needs known. One day a truck pulled into her school parking lot with dozens of desks. "We didn't know who to thank, but we knew we made a difference."

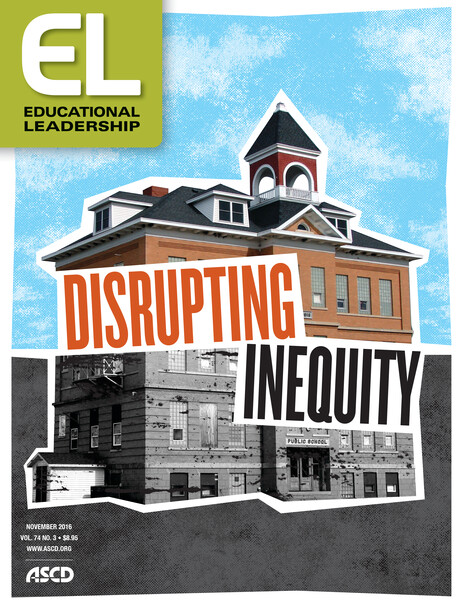

In a way, all three actions above qualify as acts of disrupting inequity—whether high-profile or low-key, effective or not yet effective. The fact is that the tragedies of recent days have provoked many people today to speak up about our need to change the status quo. This issue of Educational Leadership points out many types of school inequities—in our instruction (pp. 16, 30); in our discipline policies (pp. 42, 49, 54); in our resource allocations (pp. 36, 74, online); in our sorting and grouping of students (pp. 42, 49, 62, 70, 79, online); and in the dozens of practices that unwittingly contribute to marginalizing groups of students, whether it be because of their race, gender, religion, poverty, culture, or special needs. Our authors offer solutions, too, and chief among them is to open our eyes to others' perspectives—to see what groups can do together to remove unfair obstacles and extend fair opportunities (pp. 10, 16, 79, online).

At a recent meeting of ASCD authors here in the building, the group was asked to describe what an equitable school might look like. They described "a school where learning is a priority"; "a school to which teachers and students like to come"; "a school that respects diversity of all kinds"; "a school that has high expectations no matter the students' challenges"; and "a school that provides various pathways (not necessarily the same for all) to success for all students." They also had some catchy lines: "Equity means never saying 'those kids.'" "Fair is not always equal." "It should not matter which teacher a child gets, and it should not matter which school a child attends."

We know what we need. Now we must choose—together—thoughtful disruptions that will make equity a reality in all schools.