As a veteran language arts teacher who works with diverse students, I've found that creative writing is a highly underestimated way to bring joy—and engagement and motivation—to the classroom. Writing stories puts my middle school students in an authoritative position that's unusual for schoolwork and for young people in general. It's one place in my curriculum where students get into a state of "flow," working without realizing how much work they're doing. And when students have freedom to write in genres they love to read, they will take on challenges that they voluntarily dream up.

These are the best kinds of challenges. When students set a bar for themselves, they are motivated to reach, climb, and problem solve their way there. They ask me or their classmates for help with issues, rather than me telling them what they need to do to reach a bar I've set.

Creating the Conditions

To help students get the most out of creative writing, it helps to create the right conditions for them to feel motivated and comfortable taking risks. The trick is to find a balance of freedom and constraint for students so they can let their imaginations go without feeling overwhelmed. For starters, I don't police content. Every idea is a good idea in fiction, if you commit to it. In our first creative writing assignment of the year, students co-create prompts they'll write in response to. They help me brainstorm a list of creative-writing assignments connected to a novel or story we've recently read. The list includes ideas like changing the setting of a story, writing the beginning of a sequel, or rewriting a scene from a different character's point of view.

Being open to students' suggestions can lead to unexpected places. One year, a student asked, "Can we merge the worlds of two stories?" I was instantly skeptical, thinking, That sounds too hard. They won't succeed, and it will be a waste of time. But I reluctantly responded that, though I thought it would be a much bigger challenge than the other choices, if anyone wanted to try, I would support them.

Thank goodness I didn't succumb to my own fears, because the students who chose that assignment wrote really interesting pieces. They felt proud for accomplishing the task, and once they came up with their basic idea, the writing process wasn't much harder than that for the other choices, which had been my concern. It's good to have my policy of being open to students' ideas tested—and to have the students' ideas win.

From Slacker to Writer

Sometimes students win against their own image of themselves as non-writers. Take Efrain, for example. He was a very bright 8th grader who'd developed a pattern and identity around not trying hard in school. He made sure to pass his classes, but his efforts ended there.

In spring of 2021, after doing a few shorter fiction exercises (and after a year of remote

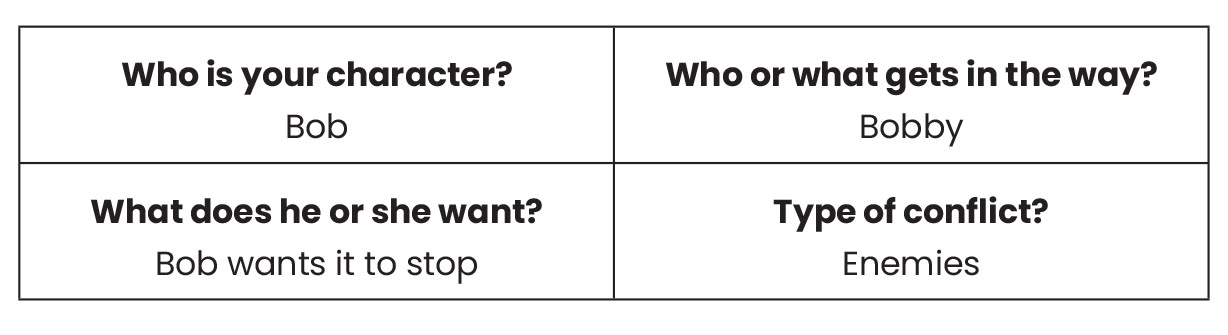

learning), my students wrote their first complete stories. Efrain's story started out as a slacker joke. The main character was Bob and his best friend was Bobby. Efrain's initial planning page looked like this:

Given his ability, this barely complete idea seemed to be telling me two things: Efrain intended to do the minimum, and he dared me to bother him about the silly choice of names for his two main characters. I called him on the vagueness of "it" on the bottom left section, but not on the names.

My instincts were correct. Try as he might, Efrain couldn't keep up his underachiever identity once he got into the creative process. By the second chapter, his narration sounded like this:

After school, Bob waited for Bobby to leave the school building so they could go to his house. When Bobby finally left, he was carrying, like, seven cups of pudding."The lunch lady was very nice," Bobby said, struggling to fit three cups into his sweater pocket."Is that what took you so long?" Bob said with a sigh."Yes. Here, take one," Bobby said as he tossed Bob a pudding cup. Bob caught the cup and said, "Let's go." They both started walking toward Bob's house. They had to stop multiple times for Bobby to pick up the pudding that kept falling out of his pockets.

The level of detail, pacing, sentence structure, and character development unleashed the brightness I knew Efrain possessed and I had wanted to see all year—but couldn't force. The story's conflict began when Bobby stole Bob's game console but didn't admit it. The climactic scene was a physical fight between the two friends standing on a bridge next to a waterfall. The physical descriptions in the scene were well done and difficult to pull off and perfectly matched the anger between the friends.

Efrain's own choices for his story, which I believe he initially intended to be an underperformance, led him to commit to the virtual world he'd created and accomplish something difficult. In one exit ticket, I asked students some questions about their writing choices and how things were going. Efrain answered:

What made you choose this character/conflict?I didn't know what to write—this was the best option.What has gone well in the writing process?I know most of what to write next, always.What was challenging in the writing process?Fixing my formatting.

I wasn't extremely involved in Efrain's writing process. I let him go on his own because, given how he had begun, I felt that my involvement might provoke more rebellion (I just peeked into his document during class to make sure he was progressing). I believe the feeling of "I know what to write next" in this story world he'd imagined created momentum for Efrain that outran his slacker stance. I'll add that formatting was a challenge for Efrain; he struggled a lot with punctuation and paragraphing of dialogue. I paired him up with a peer who had mastered the rules and could help Efrain. He accepted the help and worked to correct the formatting.

Imaginative writing is one place in my curriculum where students get into a state of 'flow,' working without realizing how much work they're doing.

Ariel Sacks

Limitations that Motivate

Often in creative work, a simple limitation opens portals for the imagination. Although I don't evaluate or control the subject matter of students' stories, over the years I've adopted two rules for stories that I truly believe make student work stronger: (1) You cannot not kill off your protagonist and (2) you cannot end with your protagonist waking up and saying, "it was all a dream." I use these rules because these plot choices tend to be overused as a way to avoid the hard work of resolving conflicts and creating character development that supports resolution. Students often try to fight me on this, but I've learned to stand firm.

Yeshi, who is usually eager to follow guidelines to a T, privately messaged me, "What if my character doesn't exactly die but is reincarnated?" Reincarnation is part of Yeshi's Tibetan culture and faith. After chatting back and forth a bit, I agreed to her idea, since in this context, death wouldn't be "the end" for her character.

She ended up writing about a character who has a conflict with her father, then slips into an alternate reality where she views her memories inside a bubble. The girl meets a spirit, Lakpa, who turns out to be her grandpa. He helps her process the memories, takes her to see the place where her father is from, and eventually helps her return to her father and the life she left. Yeshi created not only a beautiful story with character development achieved through showing, not telling, but also a window into her culture that allowed her—and her classmates—to see key aspects of that culture on the page.

Representative Literature

Another condition that supports students to take imaginative risks in their fiction is that the literature we read together and the books in our classroom library represent diverse cultures, races, religions, sexual orientations, abilities, and so on. When we read a book together, I introduce students to the author by reading a bit about them, showing students an interview with them, or sometimes meeting them virtually. Like my students, many of the authors we read are BIPOC. Reading authors that reflect the diversity of our students impacts students' mental pictures of who an author can be and what topics can be written about. When one student whose family is Haitian read American Street by Ibi Zoboi, which features a main character who immigrates to the U.S. from Haiti, he was so excited about the connections he made with the character's culture, language, and experiences. "This is my book!" he would announce. This seemed to give him a boost of pride in his work.

Transforming Pain

Sometimes students choose to write about deeply painful experiences, which is certainly motivating and meaningful—and often healing. Esther planned to write a story about a girl whose parents wouldn't let her see her best friend, but when she started drafting, the story took her in a different direction. She ended up writing about a traumatic event in her life.

As the conflict unfolded, Esther had her main character, Amy, find out her best friend has cancer. Esther added the character of Amy's brother, who had recently died of leukemia, and included flashbacks of conversations between Amy and her brother in the hospital. I began to suspect Esther might be writing from personal experience but didn't ask her. (Esther was new to our school in 2020—during a year of remote learning—so we didn't know much about her or her family.)

When we shared our stories, Esther chose to read the flashback scene in which Amy's brother dies, including the things he said to her in his last moments. As she read, there were pauses, and her voice sounded strained. I at first thought Esther's internet was spotty, then realized she was crying. I offered to read the scene for her, and then I, too, got tears in my eyes as I read. The other students were quiet, but several posted heart emojis in the chat space. We sensed that this was Esther's own truth—that she had recently lost someone close to her. The intensity was compounded by the fact that several other students had experienced devastating losses during the pandemic and were isolated from the in-person community school can offer.

At the end of the period, I talked with Esther through private chat. She confirmed that these scenes were based on her own brother's death. I offered my condolences and said I was honored that she chose to share these memories. I told her a lot of students were in pain over recent losses, and her courage in sharing hers had no doubt made others feel less alone. Esther took up the challenge of writing about her trauma because it called to her, and I believe she did it justice.

Engagement and Representation

Reading authors that reflect the diversity of our students impacts students' mental pictures of who an author can be and what topics can be written about.

Rigorous and Freeing

For my 8th graders this past year, writing fiction often felt like a lifeline. Imaginative writing was something genuine we could do online, a medium through which students gained understanding and empathy for each other. Such writing invites students into learning in a way that's both rigorous and freeing.

Note: All student names are pseudonyms.