Imagine a great class discussion. What does it look like, sound like, and feel like? Maybe you imagine yourself starting the discussion with an intriguing open-ended question, and your students begin kicking around ideas. Nearly all of the students are engaged and energized. They try out ideas, take risks, ask questions, and listen to each other with interest. You occasionally redirect the discussion or pose another question to move the discussion to the next stage, but students' voices carry the day. Their learning is collaborative, deep, and rich.

Then you actually begin class, and the opposite happens. Only a few students participate in the discussion without being prompted, and their responses tend to be short and low-level. Instead of talking with each other, students are engaging with you, and most of their "discussion" seems to be about searching for the correct answers. You seem to be doing as much, if not more, talking than all of the students combined. When you remember the adage, "Whoever is doing the talking is doing the thinking," your heart sinks.

What's going on? Why is the reality of class discussions so far from your vision of what they could and should be?

It may be any number of things. Students might not feel safe enough to risk sharing ideas with each other. Their seats might be arranged in rows facing you, making it hard to make eye contact with each other. Some students might need to warm up with some writing or a partner chat before they're ready to share aloud with the group. Perhaps the discussion required homework prep, and students (for a variety of reasons) weren't able to get their work done before class.

But there may also be another factor in play—one that you haven't considered. What if the way you talk with students is actually emphasizing compliance over engagement? What if you're sending messages to students that the real goal of the discussion isn't an interesting exchange of ideas but is instead a way to please you?

In my latest book, What We Say and How We Say It Matters (ASCD, 2020), I dig into common mismatches between our best intentions as teachers and the language patterns we use. A few simple shifts can move class discussions from exercises in compliance to ones of true engagement.

Beware of Teacher-Centric Language

You might be surprised to find that you're opening class discussions with invitations that indicate that you are the focus of attention, not the students. A telltale clue is the use of first-person. "I want to hear about …", "Show me what you're thinking about …", "I can't wait to hear your ideas …", "I'm looking for people to …."

These statements show, unintentionally, that the point of the class discussion is for students to share with you instead of each other. Participating in the discussion becomes an act of compliance, and this may actually decrease some students' motivation to share.

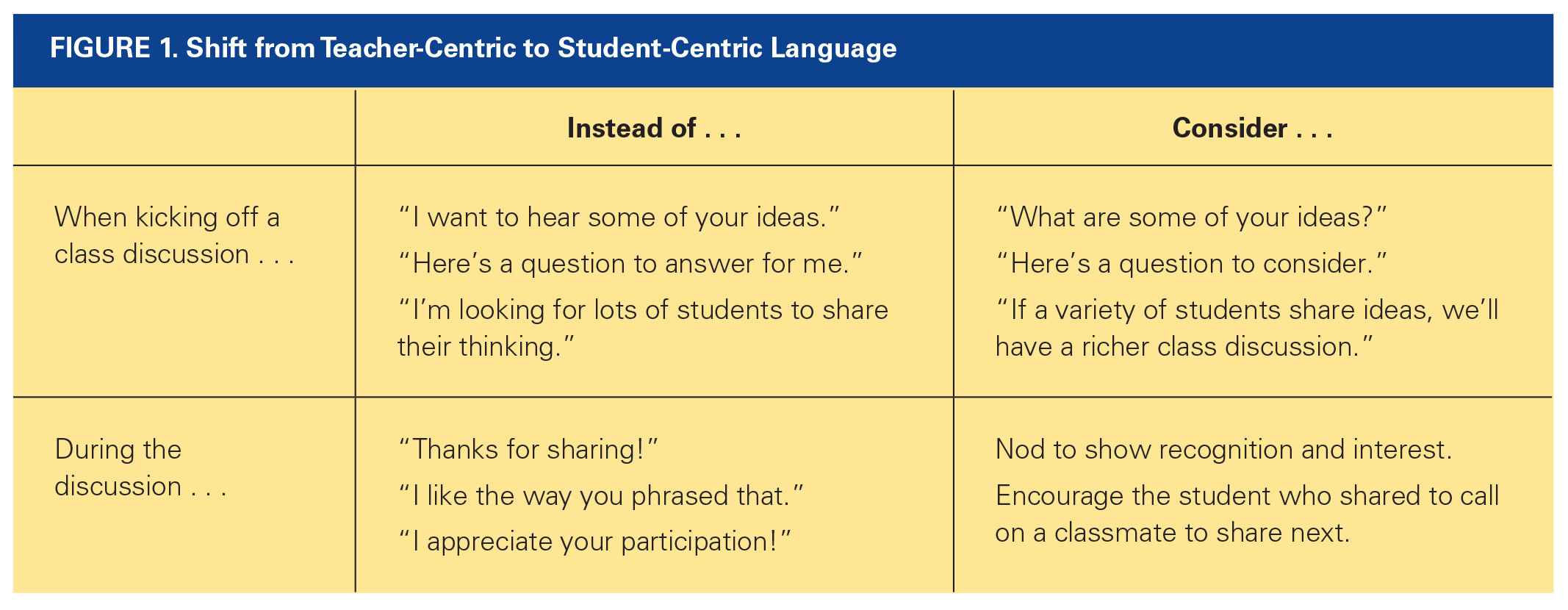

Instead, try slightly rephrasing your interjections to remove yourself from the equation. Instead of, "I want to hear your ideas," say, "What are some of your ideas?" (See Figure 1 for more suggestions.) This indicates that students are the focus, and that they should feel comfortable sharing their ideas instead of feeling like they need to find the "right" answer to please you, the teacher.

Even after the discussion is underway, teachers may continue to send messages that participation is about pleasing them. They might thank students to encourage others to share, but this could end up having the reverse effect, especially when working with adolescents who may shy away from obvious teacher-pleasing to avoid getting teased. Instead, teachers can show appreciation and engagement with eye contact, nodding, and listening with interest. To further diminish their role in the discussion, teachers can introduce a routine where, after one student shares, that student calls on the next student.

Reduce Echo Talk

Another way that educators accidentally shift the emphasis of discussions away from students is through echo talk. This is another incredibly common (and usually unconscious) verbal habit—echoing back what students say after they share. The following example shows this in action.

Teacher: What are some of the potential impacts of polar ice melting?

Student 1: Sea levels could rise.

Teacher: Yep. Sea levels could rise.

Student 2: Some coastal cities might flood.

Teacher: Coastal cities might flood.

Student 3: All of that fresh water could change the salinity of oceans.

Teacher: The salinity of oceans could change.

This language habit increases the amount of teacher talk. It also sends the message that students don't need to listen to each other since the teacher will repeat everyone's ideas. And what does it say if the teacher doesn't echo an idea? That it's not as valued? Echo talk subtly gives the message that class discussions are exercises in paying attention to the teacher rather than engaging in an exchange of ideas among students.

Sometimes teachers use echo talk intentionally to validate students' thinking—to let them know that they're being heard. Alternatively, though, educators can nod, smile, make eye contact, and send other nonverbal cues that they are paying careful attention to what students say. Teachers may also use echo talk if students speak too quietly for classmates to hear. If this is the case, they should encourage students to speak with a louder voice. They can also teach a signal for students to use (such as a hand to their ear) to indicate that they can't hear a speaker. Arranging students in a circle can also help.

Reduce Judgment

One other way to deemphasize compliance to teachers is to reduce the amount of judgmental (or value-laden) language you use during discussions. For example, have you ever said something like, "Who has a great idea to share?" Or, when someone shared an idea that you liked, have you ever responded with some version of, "Great job! That is such an important point!"?

These kinds of value statements are common, and the intentions are good. You want your students to share good ideas. You also want to encourage them to participate, and you've heard that praising them is a way to boost motivation. Unfortunately, these statements can have the exact opposite impact of what you're going for.

Imagine yourself as a student. Your teacher begins a discussion by saying, "Who has a good idea to share?" You think about your idea and wonder, Is it good? If you're not sure, you may be less likely to share it. When you hear another student praised for their idea (Yes, Jake! That's such an awesome example!), are you more or less likely to share yours? Or are you suddenly more anxious and guarded?

This kind of praise can also set a competitive tone, where students are vying for the best responses to please the teacher. So, what should you do instead? When kicking off a class discussion, you can simply omit words that indicate judgment. Instead of saying, "Who has a great idea to share?", say, "Who has an idea to share?" This simple shift can take some of the pressure off of students. You might further emphasize this by adding, "Don't worry if your idea is a good one or not … we need to share lots of ideas so we can think about a variety of possibilities."

Once again, as students share ideas, try to minimize the amount of talking you do. However, don't remain silent for the whole discussion. You may need to interject another question or add another idea to keep things moving forward. ("Many of you are focusing on this one key point. Here's another idea to consider ….") You might need to get a discussion back on track if it starts to head down an unproductive path. ("Let's see if we can refocus on the main idea of our discussion ….") These statements continue to focus students' attention on the discussion as opposed to your thoughts and feelings about the discussion. They continue to emphasize engagement with the discussion over compliance with the teacher.

Changing Language Habits

Without meaning to, when teachers frequently use teacher-centric language, echo students' ideas, and use judgmental language, they indicate that class discussions are all about them. By shifting these habits, educators can emphasize student ownership of ideas, create cultures of safety and collaboration, and swing the ratio of teacher-to-student talk in favor of students.

It's hard to shift language patterns, so if you decide to make a change, focus on one habit or pattern at a time. Ask yourself, "How might my students benefit if I make this shift?" Then choose a concrete strategy to help you practice. You might create an index card with language you're trying to use that you can hold as you teach. Or, tell a colleague your goal and ask them to observe you as you facilitate a discussion to give feedback and suggestions.

Finally, be patient with your students as they adjust to a new paradigm. You can't expect them to adjust their discussion behaviors the moment you change your language. They'll need time to internalize the new messages they hear. As you become more consistent with your language habits, you'll see students shift their focus and extend their participation—bringing you closer to the ideal class discussions you're working toward.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ Do you find yourself using teacher-centric language during discussions? How might you change that?

➛ When a discussion isn't taking off during class, what strategies do you use to move the conversation deeper?

➛ What one shift in language or behavior could you make to turn the focus on your students during discussions?