For many students these days, the outdoors have become a haven for creativity and a welcome break from rising screen time. Nature journaling is a wonderful way to get students outside this spring. It can improve well-being and lengthen attention spans, while also developing students’ writing, research, and scientific observation skills.

Nature journaling gets students to explore, and to perceive and feel the world around them and their place in it. I have integrated nature journaling activities for students in my elementary, middle school, and undergraduate classes, and have found that students in each age group are equally engaged and appreciative of the time to slow down, connect with the natural world, and reflect on their lives and the living world.

As a researcher, I worked with 3rd and 6th grade teachers at a Title I elementary school in Arizona who implemented weekly nature journaling into their curriculum for a semester. I provided staff with initial guidance and suggestions but encouraged them to design prompts that worked for their students.

We found that some students felt more at ease developing their writing skills through nature journaling. They also gained new science knowledge and included more details in their observations and writing, their teachers reported.

Here are some reflections from the 6th graders:

“Nature journaling is really fun. Because, you know, you could just express yourself on paper.”“Writing out here inspires you a lot more. It's much more exciting. It's much nicer. It really does give you just a lot more of a reason to write.”“It helps us get out of our mind, from stressing about what we have to learn about. You get to be more free about it than just stressing about the tests.”

Through such experiences, I have found that the following three strategies work best, for me and other educators, to get students to journal effectively outdoors.

1) Set the Nature-Journaling Stage

Before the writing begins, share biographies of naturalists such as Rachel Carson, Louis Fuertes, or John C. Robinson to motivate and inspire students. Then, make sure each student has a small notebook with blank pages (ideally one that opens flat) and colored pencils. Digital devices can be used when available to take photographs.

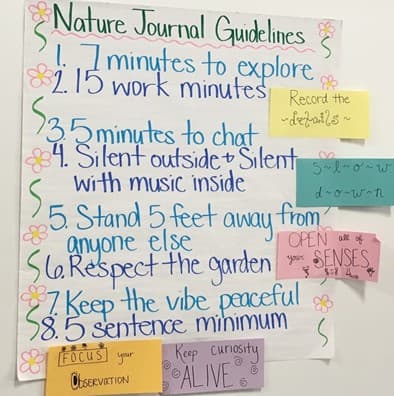

To help students distinguish nature journaling from recess and other outdoor activities, create nature journaling norms with them (see fig. 1 below). These can be written on chart paper or in the front of their journals. Review these norms as needed to develop a routine and shared expectations—and remember that some students will need more reminders than others.

TIP

Allowing students a few minutes to walk around and explore before settling into writing helps them release pent-up energy.

Figure 1. Nature Journal Guidelines Example (6th Grade)

Credit: Eileen Merritt

2) Support Student Autonomy when Journaling

Nature journaling opens up possibilities for student choice. Let students decide where they want to write. Some may pick an inspiring plant or tree to sit next to and others may opt to sit directly in the sun.

The following strategies can also be used to increase students’ autonomy:

- Create open-ended prompts (examples below) that allow students to bring their background knowledge and creativity to the process.

- Allow students to combine writing, drawings, diagrams, or even photographs to express themselves. Be open to what emerges from nature and in their writing.

- Allow students to go “off script” if they are engaged with a topic or idea.

As an educator, you can change the writing prompt or direction if something emerges in the natural world that takes you and your class in a new direction. Teachable moments such as a bird landing in a nearby tree, or a desert tortoise emerging from its home, can be useful in guiding observations about animal adaptations. Above all else, be flexible. For example, as one 6th grade student said, “You should let kids be able to do whatever they want with those prompts, as long as it even just slightly ties into the prompts . . . let them get completely creative.”

3) Choose Prompts That Inspire Connection and Reflection

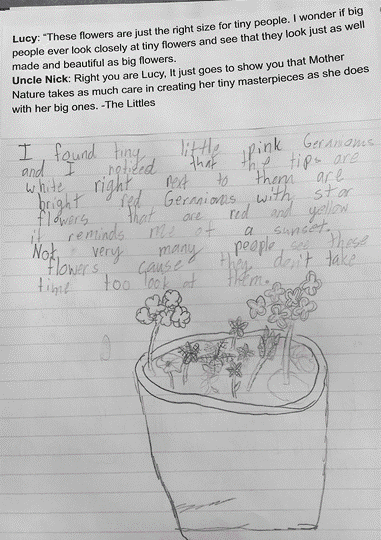

Simple open-ended prompts such as “I notice . . . ” and “I wonder . . . ” and “This reminds me of . . . ” as described in the book, How to Teach Nature Journaling, can guide students to find something that captures their interests (an organism, a phenomena, or even a nonliving element in an ecosystem). They can describe it, write questions about it, and consider how that object or process connects to something else they know. Nature journaling can be used to deepen observation skills or to inspire awe and wonder. A 3rd grade teacher used a quote from book The Littles to inspire a journal entry (see fig. 2). She shared the quote with her class, then asked students to find a tiny masterpiece in the school garden:

Figure 2: Journal Entry Example (3rd Grade)

Credit: Julia Colbert

One 6th grade teacher saw nature journaling as a place for students to express their emotions while also connecting to the natural world. The prompts below inspired her students to reflect on connections between nature and their own lives.

- Find a plant that models how you’re feeling today (your emotions).

- Draw a picture of something in the school garden that matters to you and write about why you feel that connection.

- Choose a favorite plant that connects to you/who you are/how you feel. Describe how you are the same or different and why.

Nature journaling activities are easy to find, but part of the joy in this work is writing prompts that capture what’s happening in the natural world and in the lives of your students. For example, one teacher had her students go into the schoolyard on a foggy morning and journal about fog, which yielded a lot of descriptive writing. Similarly, I designed the following prompt for undergraduate students in a course I taught called Ecology and Natural History of the Sonoran Desert.

Find a Saguaro cactus that reminds you of yourself. Share a picture of that Saguaro and describe WHY it reminds you of yourself. Use a simile or metaphor in your response.

When I discovered Saguaro cacti for the first time, I was struck by the uniqueness of each individual organism, and was not disappointed when students wrote rich descriptions of Saguaro features that reflected themselves.

Nature journaling activities are easy to find, but part of the joy in this work is writing prompts that capture what’s happening in the natural world and in the lives of your students.

Eileen Merritt

An Ongoing Process

This spring, consider adapting the strategies described above to your students and schoolyards. Be patient—it may take students time to get into the routine of nature journaling, and quiet their minds to make space for writing. Some of them will need scaffolding, such as sentence starters or having a teacher serve as their scribe, jotting down some initial thoughts for them. Remember, some students will prefer to express themselves artistically, with fewer words. Drawing is a wonderful way to represent organisms and their relationships—the words may come later. Take away the pressure of grading by just providing them with feedback on their work and allowing students to share their observations with others. Encourage students to select a favorite response to “publish” or finalize a particular entry for a grade to document learning.

The Takeaway

Nature journaling is more than just taking students outdoors to write. It is establishing a regular practice of finding a quiet space for students to observe what is happening in their environment, and document what they see and feel. To set students up for success, it’s important to establish journaling norms, support their autonomy when possible, and guide each session with prompts that align with specific goals. Outcomes such as enjoyment, attention restoration, and stress management are equally important as the improvement teachers will see in scientific observations and descriptive writing. The beauty of this interdisciplinary practice is that with the right balance of autonomy and structure, you can accomplish academic and social-emotional learning goals at the same time.

More Resources

John Muir Laws has written several nature journaling books, and most recently a how-to guide for teachers. Check out the books, example journal pages, and lessons for teachers and students on his website.

The Nature Journal Club on Facebook provides examples of nature journal pages from thousands of members, which teachers can share with students for inspiration.

Books by Claire Walker Leslie, a naturalist, artist, and educator, include ideas and beautifully illustrated examples of pages on different topics.

Virginia Wright-Frierson, an author and artist, has written several read aloud books for elementary students that include journal excerpts with drawings and descriptions of organisms in specific ecosystems. See, for example, An Island Scrapbook, A Desert Scrapbook, and a North American Rain Forest Scrapbook.

Note: The research summarized here was conducted in partnership with Julia Colbert and Jason Papenfuss, along with educators and students at Echo Canyon School.