It’s hard to miss the meteoric rise of the Wordle craze. This game is not only a gift for lexophiles but also for educators. It reminds us that effective phonics and spelling instruction requires carefully designed, explicit teaching combined with volume reading, vocabulary building, and high levels of engagement.

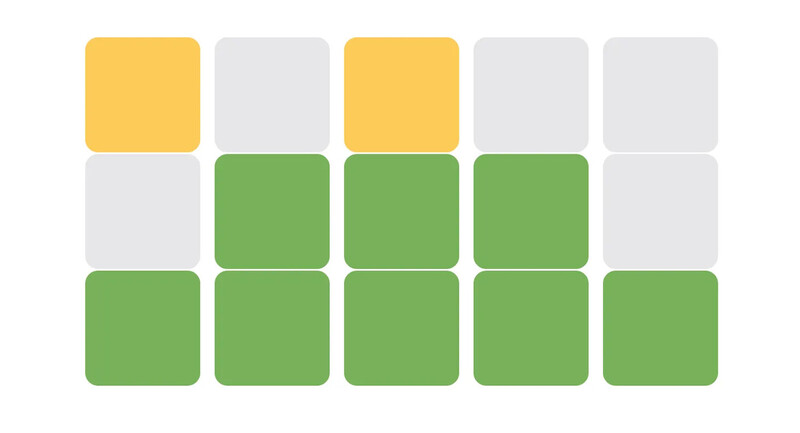

The object of Wordle is to guess a five-letter word in six attempts. After each attempt, the game tells you which of the letters you guessed are in the word in the right place, which letters are in the word but in the wrong place, and which letters are not in the word at all. With 26 letters in the English alphabet, the game would be nearly impossible as a purely statistical exercise. But knowledge of English orthography (how words are spelled) puts the challenge within reach. Studying how to be successful with Wordle can be helpful to educators because it can remind us of some key points about effective phonics and spelling instruction. Here are the top five Wordle reminders that can boost literacy instruction.

1. Some letters are more common than others.

That some letters are more common than others is well known to players of Scrabble (think letter point values) or Wheel of Fortune (think of puzzle-starting r, s, t, l, n, e). Wordle players—I’ll call them Wordlees—likely know this too. They’re unlikely to play jazzy as their first word, whereas raise is a logical way to start.

Variation in letter frequency is one of many reasons why educators should not teach the alphabet in order beginning with A, and so on to Z. Rather, promising approaches to alphabet instruction design a sequence based on letter frequency and other contributors to letter difficulty, and they spend more time teaching some letters than others based on the letter’s difficulty and children’s instructional needs.

2. The position of letters in a word matters.

Wordlees would consider placing ld at the end of a word (e.g., child), but would not consider placing it at the beginning of a word. The position of letters in a word matters. Although early on we teach children to associate the letter y with the /y/ sound, as in yo-yo, not long after in our scope and sequence, we need to teach children not to make that association at the end of words, lest they struggle to read words such as my and penny.

Wordlees were probably never explicitly taught that we don’t begin words in English with ld. Rather, they learned this and many other things about English orthography from lots of exposure to a large body of words. Statistical learning from volume reading of texts in the language(s) one is learning to read, along with explicit instruction, is critical to word reading and spelling development.

3. Letters and sounds don’t have a one-to-one match.

There are Wordle-eligible words in which there are five letters and five sounds, such as blast, but Wordlees will not be successful limiting themselves to those words. Rather, they must recognize that multiple letters can represent a single sound. For example, the word tough has five letters but only three sounds (/t/ /uh/ /f/), while the word thigh has five letters and two sounds (/th/ /ī/). One might think that the Wordle-eligible word queue is just one sound, as it is the letter name of the letter Q, but there are actually two sounds in the name of the letter Q (/k/ /ū/), as in most letter names in English (F = /eh/ /f/; G = /g/ /ē/), an important understanding for educators who teach reading.

Effective phonics and spelling instruction in English requires explicitly teaching the complex system of how letters and sounds relate. Letter-by-letter decoding is OK early on, but soon learners need to be looking at the letters around a letter—for example, s usually represents the /s/ sound, but if followed by h, we typically have the /sh/ sound. Some patterns require readers to look even further ahead—for example, to associate dge with /j/ and eigh with /ā/. Similarly, spelling development in English requires understanding that there are sometimes many different ways we can spell the same sound (e.g., eigh, a_e, ai, ay, ey. . .).

4. Vocabulary knowledge is important to word reading and spelling.

It doesn’t take long playing Wordle to recognize that the larger your vocabulary, the better you are likely to do. You might easily think of words such as great and happy, but can you think of bezel or jugum?

We typically need to have a word in our vocabulary to even think to use it in our writing, and knowing the word’s meaning can give us valuable hints about how to spell it—for example, spelling electrician rather than electrision. Explicit teaching of meaningful word parts (morphology) supports spelling development. Similarly, vocabulary knowledge helps us to read words—when we come across lemic, do we pronounce it with a short e, like lemon, or a long e, like lemur? Having the word lemic in our vocabulary would tell us. Of course, we need vocabulary knowledge not only to read and spell words, but to monitor and develop our comprehension and composition.

It doesn’t take long playing Wordle to recognize that the larger your vocabulary, the better you are likely to do.

Nell Duke

5. Phonics and spelling can be engaging.

Wordle is highly engaging—some might say addictive. It has many characteristics long associated with motivating and engaging literacy experiences, such as being challenging but attainable, being social (at least potentially), and having a result or consequence.

Engaging with phonics and spelling can be highly engaging for children as well. One research-supported instructional technique for developing word reading and spelling called word building is not that different from Wordle. For example, young children might build sat, sap, tap, top, stop, and so on. Tim Rasinski, a professor of literacy education, incorporates meaning-based clues into word building. For example, from the word “dart,” he asks students to “change one letter to make another word for soil or earth” (dirt).

Engagement deepens further as children actually deploy their developing phonics and spelling abilities to read and write texts to inform, persuade, entertain, and innovate.

Who knows—maybe one of your students will invent the hottest thing since, well, Wordle.

Related Resource

Do you want to read more instructional strategies from Nell Duke? Don't miss the November 1, 2020, EL article "When Young Readers Get Stuck."