For students to learn to think critically and deeply, we have to change the one-directional paradigm of teaching and learning that often prevails in classrooms. Educators should view students not as empty vessels for the transfer of information but as knowledge builders in their own right. We need to share influence in the classroom rather than hoard it. Through these mindset shifts, we can cultivate a pedagogy of student voice. Knowing how to think critically takes practice, and each learning moment that centers student voice and inquiry creates a training ground for this lifelong skill.

In creating this kind of learning environment, we can take a cue from Indigenous cultures, in which learning "involves generational roles and responsibilities" and is "embedded in memory, history, and story" (Chrona, 2022; First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d.). According to scholar Lorna Williams (2018/19), elders in Indigenous communities are often called "knowledge keepers" because they keep and record knowledge through stories, songs, dances, and other memory tools. Extending this concept to the classroom, we can view teachers as facilitators of learning who can connect their students to knowledge keepers in the community while simultaneously viewing students as knowledge builders—fellow storytellers engaged in a reciprocal learning journey (Augustine, 2022).

Indigenous pedagogy has much to teach us about what it looks like to discuss ideas with others in probing yet respectful ways.

Indigenous pedagogy has much to teach us about what it looks like to discuss ideas with others in probing yet respectful ways. In the Hawai'ian language, a'o is the word for the exchange of expertise and wisdom, where sharing is cyclical and results in shared action (Galla & Goodwin, 2017). Such a learning environment is rooted in humility and listening, often requiring teachers to decenter themselves as the primary source of knowledge in the room.

What if we viewed our role as educators as cultivating learner voice and agency through spaces of distributed knowledge? What if we saw students' voices, stories, work products, and experiences as primary texts for our own deep learning—what Jamila Dugan and I call street data, or qualitative data on learning and equity, including stories, artifacts, and first-hand observations, that often emerge at eye level (Safir & Dugan, 2021). What if with each instructional decision we made, we asked ourselves: How can I center student voice and thinking right now?

Igniting Curiosity and Intellect

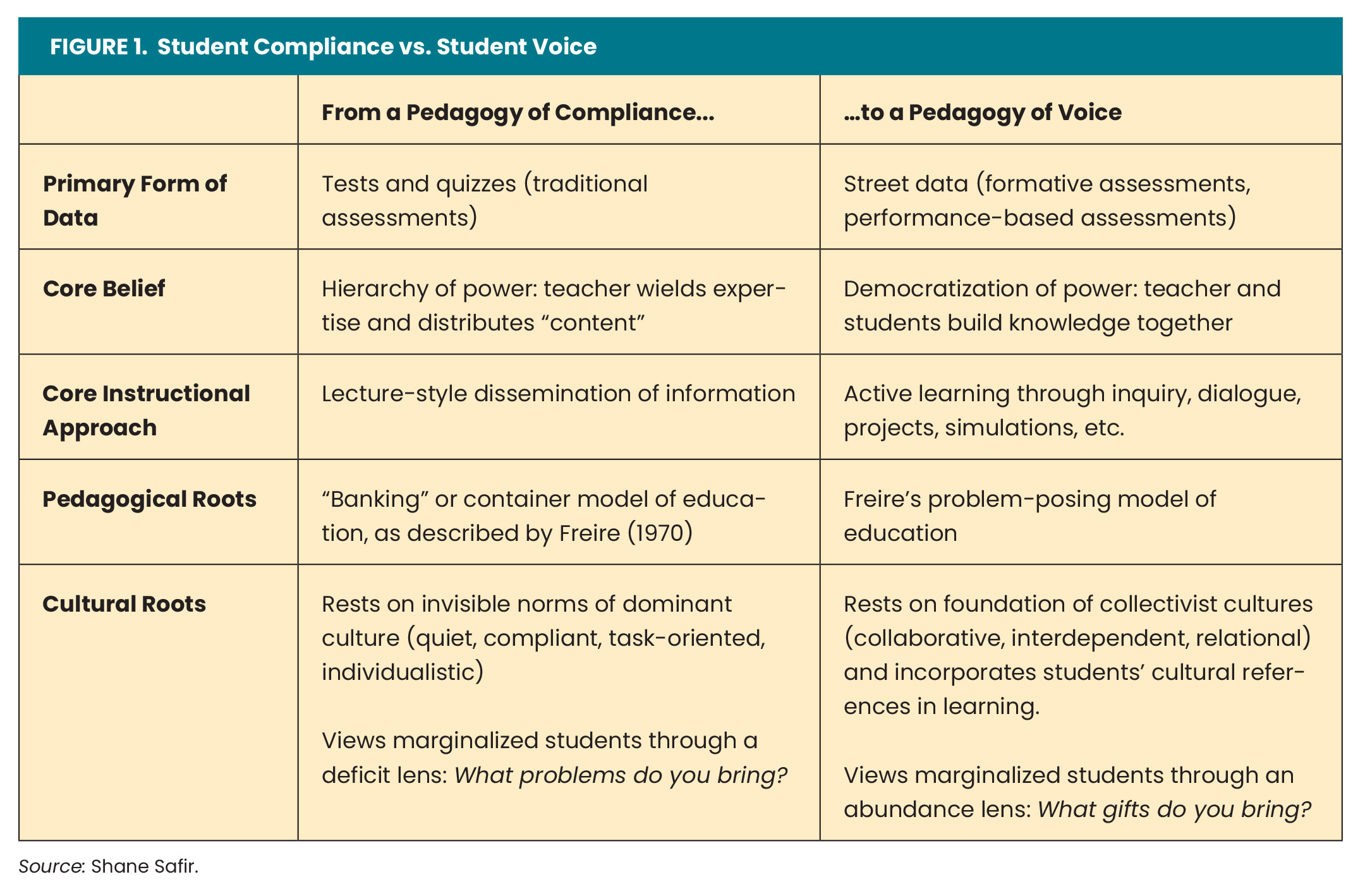

As we consider the concept of students as knowledge builders, we can reorient our pedagogy in ways that transform power in the classroom and ignite the natural curiosity and intellect of young people. A pedagogy of voice emerges at the intersection of critical pedagogy (Freire, 1970) and culturally responsive education (Gay, 2002; Ladson-Billings, 1994), offering an instructional framework and way of being that shifts the locus of learning and cognitive load toward the student. A pedagogy of voice orients us to create learning experiences that foster connection, cognitive growth, and student agency, which we define in Street Data through the domains of identity, belonging, mastery, and efficacy. It centers student voice through dynamic dialogue and rich student work, and it decenters—though doesn't necessarily eliminate—the role of compliance, grades, the quest for "answers," competition, and other features of conventional classroom culture.

A pedagogy of compliance, by contrast, continues to dominate in many classrooms—characterized by lecture-style instruction, students sitting in rows or grids looking toward the teacher as knowledge distributor, and teachers carrying much of the cognitive load. This model minimizes instructional conversation among teacher and students and leads to high levels of disengagement. According to a Gallup poll, only 53 percent of our nation's students report they are engaged in school, as measured by student responses about their enthusiasm for school, whether they feel well-known, and how often they get to do what they do best. Latinx and African American teens report even higher levels of disconnection (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012; Gallup, 2014).

Figure 1 breaks down some basic shifts from a pedagogy of compliance to a pedagogy of voice.

Ways of Being

Embracing a pedagogy of voice means breaking with long-dominant conventions in education—but educators can start by making basic changes in perspective and approach. Let's consider a few ways of being that I've found can help educators create more dynamic, holistic, and equitable classrooms.

1. Talk less, smile more.

Why is it important to "talk less, smile more," as Aaron Burr counsels a young Alexander Hamilton in Lin-Manuel Miranda's famous musical? As long as teachers do the talking, we are carrying most of the cognitive load. We are doing most of the thinking. We retain power and inhibit the growth of student agency. We can shift the cognitive load to learners by designing curriculum around probing, reflective questions and providing ample time for discussion. My personal rules as an educator:

Never talk more than 10–15 minutes without pausing for information processing and/or reflection: think-pair-share, turn and talk, journaling, walk and talk, trio discussion, etc.

Design lessons so that learners have the majority of the learning block for reflection, peer-to-peer conversation, and independent work.

During learner-to-learner conversation and group work, circulate, coach, and ask more questions. Model a culture of inquiry and don't let students wait passively for "answers."

What about the "smile more" part of Burr's advice? When we smile and employ our tone and other nonverbal cues to convey warmth, we signal to students that they are safe, welcome, and able to take risks. For students who have been marginalized, this is crucial. Talking less and smiling more helps us communicate to every child, "You are seen and loved here."

2. Prioritize questions over answers.

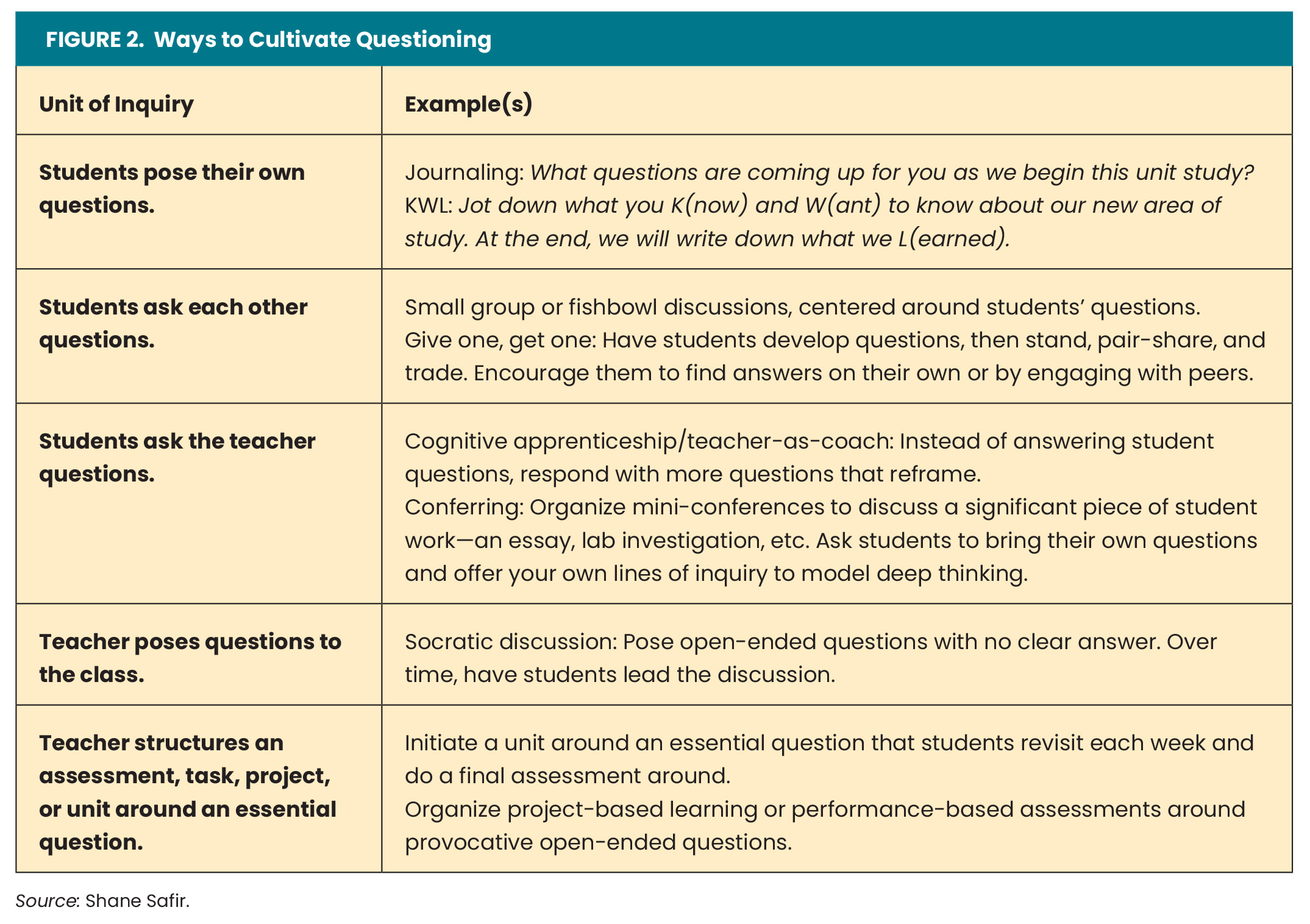

Children are naturally inquisitive. A recent study led by British child psychologist Sam Wass found that children ask an average of 73 questions per day! (Steingold, 2017). Their questions often have the characteristics of effective knowledge-building inquiries: They are important, interesting, and don't have a clear answer. To shift the cognitive load in classrooms, we have to create a culture of inquiry in our classrooms, which begins with prioritizing questions over answers in multiple and dynamic ways. When we begin to invite and even design curriculum around students' authentic questions, we create the conditions for deeper learning and the opportunity for young people to build knowledge on issues that matter to them.

We can invest more energy in developing sharp, intriguing, rich questions at every level of the learning experience. Figure 2 shows some examples of the varied use of inquiry.

3. Ritualize reflection and revision.

Centering student voice doesn't mean we stop giving feedback, but it does mean we shift our role from expert lecturer to expert coach, where our role is to cultivate students as knowledge builders. Reflection and revision are two of our strongest tools in this regard and can take place regularly throughout a unit. Here are a few approaches to play with:

Teach reflection and revision as explicit skills and processes. Consider this core content and model it in your instruction. For example, bring in a piece of your own writing and facilitate a public revision process with students. Ask students to reflect on or share a time when they had a challenging experience and found a lesson in it. Regularly showcase student work—anonymously or with the learner's permission—to "workshop" through a revision together, discussing as a class the strengths and possibilities for growth and expansion.

Begin a class period with time for students to reflect in writing or a turn and talk: What did you learn yesterday that stuck with you? What's a concept that still feels confusing?

End each week with a reflection protocol: What did I learn this week? What's one thing I feel proud about? What's one thing I'm still struggling with?

Have students share their responses in small, ongoing peer groups and close with each student giving the peer to their left or right an appreciation.

Provide students with graphic organizers and structured protocols for giving each other feedback on their work. Teach them to give sandwich feedback, starting with specific affirming comments, followed by one or two pointed critiques or suggestions and closing with words of appreciation.

When possible, make time for one-on-one conferring with students on their work. Conferences can provide the most impactful learning moments.

Allow multiple opportunities for students to revise their work, redeem their academic status, and grow their skills to demonstrate learning (Darling-Hammond, 2002).

4. Make learning public.

One of the quickest ways to embrace a pedagogy of voice is to put students in the driver's seat by having them design and teach select lessons. You can also build entire units and projects around culminating exhibitions or performance-based assessments where students demonstrate their understanding for a larger audience. These can be powerful experiences of public learning, especially when grounded in a holistic assessment system that is based on common schoolwide standards and integrated into daily instructional decisions. Such a system shows students what they need to do by providing models, demonstrations, simulations, and exhibitions of the kinds of high-quality academic work they need to produce.

One of the quickest ways to embrace a pedagogy of voice is to put students in the driver's seat by having them design and teach select lessons.

Here are a few examples of public learning that you can experiment with in your classroom, grade-level team, department, school, or district:

Portfolios of student work that showcase in-depth study via research papers, original science experiments, literary analyses, artistic performances or exhibitions, mathematical models, and more.

Rubrics that represent explicit, simply worded, shared standards for assessment and can be used collectively by students and teachers to practice critiquing student work, in small groups or as a whole class.

Oral defenses by students to a committee of teachers, peers, and even community members that allow educators to listen for in-depth understanding.

5. Circle up.

The structure of compliant classrooms is painfully predictable: students in rows (or other grid-like organizational patterns), plugged into individual desks like widgets, taking notes while the teacher does most of the talking. This scene implicitly communicates to students their voices don't matter, their cultural schema and knowledge are tangential at best, and their job is to get "filled up" by the expert at the helm. By contrast, reshaping our classrooms into circles communicates equality of voice and membership in the community. Circle gatherings, another indigenous concept, represent the village coming together for dialogue and signal to the learner: "You belong here, just as everyone around you belongs here. I want to see your face and hear your voice."

You can disrupt the pedagogy of compliance by reshaping your learning around a circle in numerous ways:

Conduct Socratic seminars, a structure for inviting students into a physical circle to explore a shared text (which could be a literary work, a photograph, work of art, or math problem) through provocative questions and dialogue. This type of circle is rooted in the core belief that a single question should lead to further questions, like tributaries in a river.

Create concentric circle activities in which an inner group of learners faces outward, and an outer group faces inward, forming discussion pairs. One circle rotates each time the teacher offers a new prompt, or question, for dialogue.

Provide time and space for science lab experiments or mathematical modeling where students huddle around a table.

Allow design-build projects where students gather around materials and a design challenge.

6. Favor feedback over grades.

Finally, a pedagogy of voice requires us to break the stranglehold that grading has over classrooms across the country. As a parent and educator, I see teachers lost in algorithms, equations, and formulas that strip critical judgment out of teaching and learning. By contrast, feedback helps us remember that learning is messy, in the best possible way!

A pedagogy of voice requires us to break the stranglehold that grading has over classrooms across the country.

Every moment in the classroom is an opportunity to gather street data on the cognitive complexities of learning—the aha! moments, the stumbling blocks, the bursts of creativity, the spirals of self-doubt and shame, the neurological effects of stress and trauma, the sheer joy of understanding something new. Rather than contribute to our understanding of what's getting in the way for students, a narrow focus on grades often creates added stress and emotional pressure, particularly for children with learning differences and those struggling to catch up to grade level.

Here are a few ways to elevate feedback over grades:

Stop grading homework. Homework should be framed as low-stakes practice on new skills, not a hammer to promote compliance or punish children who struggle to get it done.

Stop measuring participation. Participation grades are rife with bias, inviting unconscious discrimination against students with attention challenges or cultural/communication styles that don't mirror the teacher's.

Allow late work. One principal I know established a three-day grace period for every student for every assignment. He explained it like this: "The penalty for not doing the assignment is doing the assignment!"

Allow redos and retakes. Any student should be able to retake a major assessment for a full new grade as long as they are coming to school and putting in basic effort. (This also tacks to the culture of revision discussed earlier.)

Use descriptive, criterion-based rubrics instead of points. Points promote a culture of bean-counting and competition, whereas rubrics, when well-crafted, promote reflection and development.

Use grades to summarize student achievement over time, after the child has had ample opportunities to redo and revisit work.

Make time for narrative feedback and student conferencing, whenever possible. If your student load is too high, teach students to do this with each other in structured peer conferences.

Daily Practice for Deeper Learning

The six simple rules of a pedagogy of voice can help us shape small moves at the classroom level and big moves in curriculum and assessment design. Together, they will help you cultivate a pedagogy of voice rooted in the belief that students are knowledge builders and that our role as facilitators of learning is to offer a daily practice field for deep and critical thinking.

Parts of this article were adapted from Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation by Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan (Corwin, 2021). Reprinted by permission of SAGE publication, Inc.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ In what ways could you better position students as knowledge builders in your classroom or schools? Why do you think this is important?

➛ Do you agree that a "pedagogy of compliance" continues to prevail in many classrooms? If so, why do you think this is?

➛ What steps could you take to heighten the roles of reflection and revision in your classroom or school?