Each September, our English department asks students to write diagnostic essays to get a sense of their writing skills. Depending on the prompt, they usually write about multiple characters in a short story or a few reasons why cell phones should be banned from the classroom. While the individual ideas in the essays are promising, the overall effect is superficial—students write about a number of characters or reasons, but none in depth. They skim the surface of the subject, avoiding a deeper, more complicated consideration of any particular character or individual reason. In other words, they write typical versions of the five-paragraph essay.

The persistence and effects of the five-paragraph essay—a widely taught school form where student writers offer three supporting examples sandwiched between an introduction and conclusion—have been well documented (Boecherer, 2018; Campbell & Latimer, 2012; Rorschach, 2004), but my concern lies less with its form and more with the superficial thinking that it encourages.

"When I carefully read my students' essays for depth of content," laments Elizabeth Rorschach (2004), "I find myself terribly disappointed by how shallow and un-thought-out most of the five-paragraph essays are." Indeed, five-paragraph essays lead students to "do away with complex, even messy, arguments in favor of simple theses that can be proven quickly and without counterargument" (Boecherer, 2018, p. 88).

I've seen this type of superficial, simplistic approach in my students' work, and I've begun to push them to think further. My feedback to students on their diagnostic essays is usually about asking them to focus in on their subjects: to write about one character—or, even better, one aspect of one character—or one reason cell phones should be banned from the classroom. This renewed focus demands more thought and specificity from the writer. As Wendell Berry observed, "The discipline of thought is not generalization; it is detail" (2002, p. 87).

My methodology for teaching students to think more deeply, and therefore with more complexity, can be articulated in a mantra: With focus comes depth; with depth, complexity.

My methodology for teaching students to think more deeply, and therefore with more complexity, can be articulated in a mantra: With focus comes depth; with depth, complexity. It is a concept continually practiced and reinforced throughout the year—in assignments, in class discussions, in formative writings, in revision work, and in longer, research-driven writings. The phrase frequently appears in my direct instruction and in my verbal and written feedback to student writers.

In the spirit of focus, I will use excerpts from a research paper written by one of my former 11th-grade students as a representative example. Ella's first draft was 11 pages long, but in its simplicity and superficiality, it still represented the five-paragraph essay form. Her second shifted to focused, in-depth, complex writing. The transition between the two provides a road map for making such a shift.

Ella's First Draft: Writing Just Below the Surface

Ella chose to center her year-long, research-driven writing project on the character Belle from Beauty and the Beast. In particular, she was responding to critics who claimed that Disney princesses were not good role models for girls. So far, so good—she was responding to a generalized assertion by writing about a particular princess.

But the piece quickly lost focus, beginning with her title: "I Want So Much More Than They've Got Planned: Examining Disney's Princess Belle as a Feminist Role Model for Adolescent Girls." Because no one reason is given for Belle being a feminist role model, we can assume that Ella will write about several.

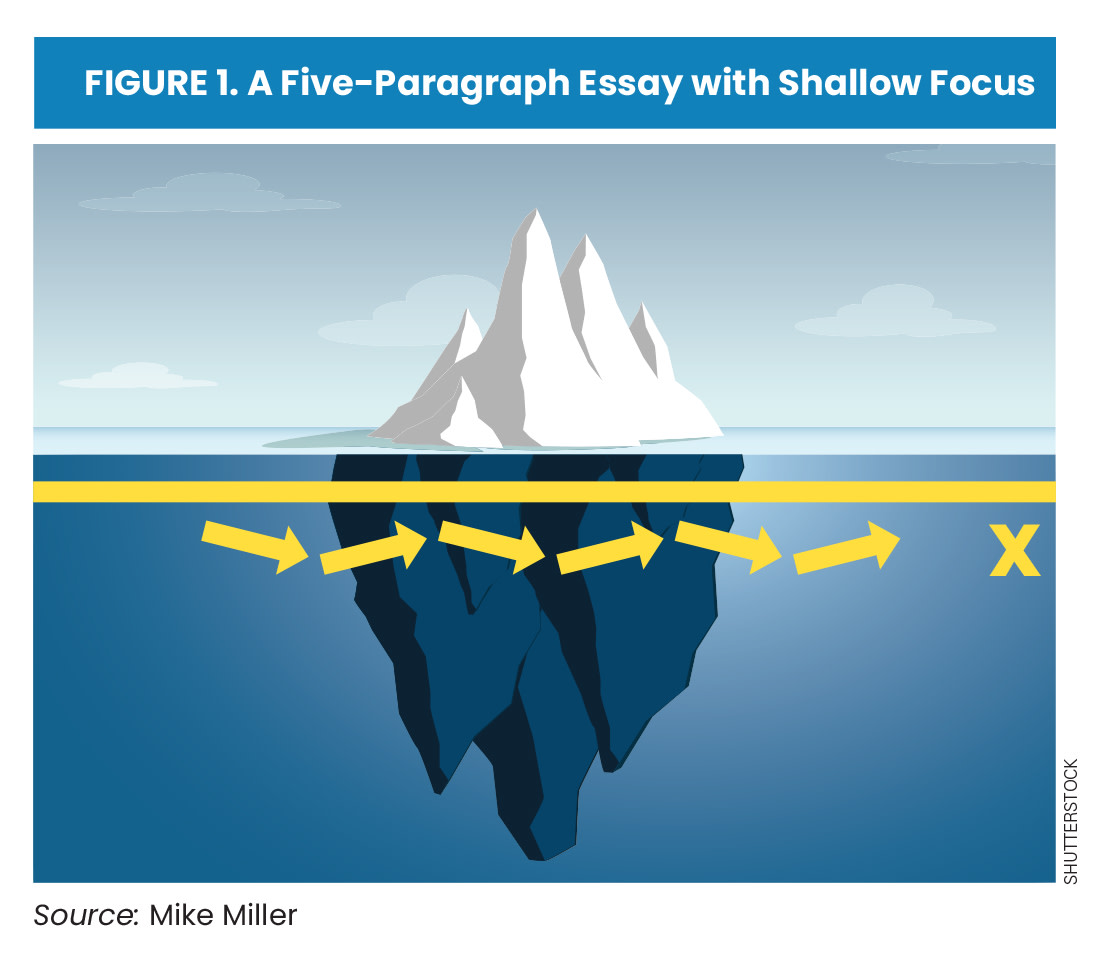

Indeed, Ella does write about several reasons that Belle is a feminist role model, and her first draft follows the typical depth and direction of a five-paragraph essay, as illustrated in Figure 1, with the X axis representing surface-level thinking. Ella begins to delve into a particular idea ("In spite of the fact that Belle does voluntarily submit herself as the Beast's prisoner, and is subjected to harshness from the Beast, she does not fall in love with an abuser, or show that abuse is acceptable"). But rather than pursuing and developing that idea in depth, she returns to the surface to introduce another idea, or additional ideas. ("Belle is a good role model for a variety of reasons; for example, she is more mature than other princesses, and often regarded as the ‘intelligent' princess.") This pattern repeats itself throughout the course of the essay.

In her paper, Ella introduces counterarguments: "Sumera goes on to say that ‘in spite of [Belle's] feminist quality of being learned and educated through reading, her predilections for romance uncover the mask of feminism,'" but she does not allow them to complicate her assertion. Instead, she repudiates counterarguments in absolute terms—"She also does not have any ‘predilections for romance,' as none of her actions in the film reflect this." This oversimplifies her argument.

"Too often," notes scholar Janet Bean Thompson, "inexperienced writers avoid writing about the things that confuse them. Fearing the ambiguous, they overlook troublesome passages in favor of easy generalizations. They feel they have enough problems with reading without creating more for themselves" (1990, p. 175). Like a lot of students, Ella had likely come into class thinking that a good argument was an absolute, decisive argument—one that never wavered in its certainty. As a high-achieving student in her junior year of high school, she had enough on her academic plate without authentically grappling with questions in this essay that might undermine her argument.

Ella's Second Draft: Digging Deeper

When I conferenced with Ella about her first draft, I suggested that she focus the piece more closely. There are many reasons that Belle might be a good feminist role model, but which one should be pursued in depth? Ella decided that she would focus on Belle's reading. Her revised title suggests improved focus and complexity: "Beauty and the Book: How Disney's Princess Belle Is a Good Feminist Role Model Despite Her Reading."

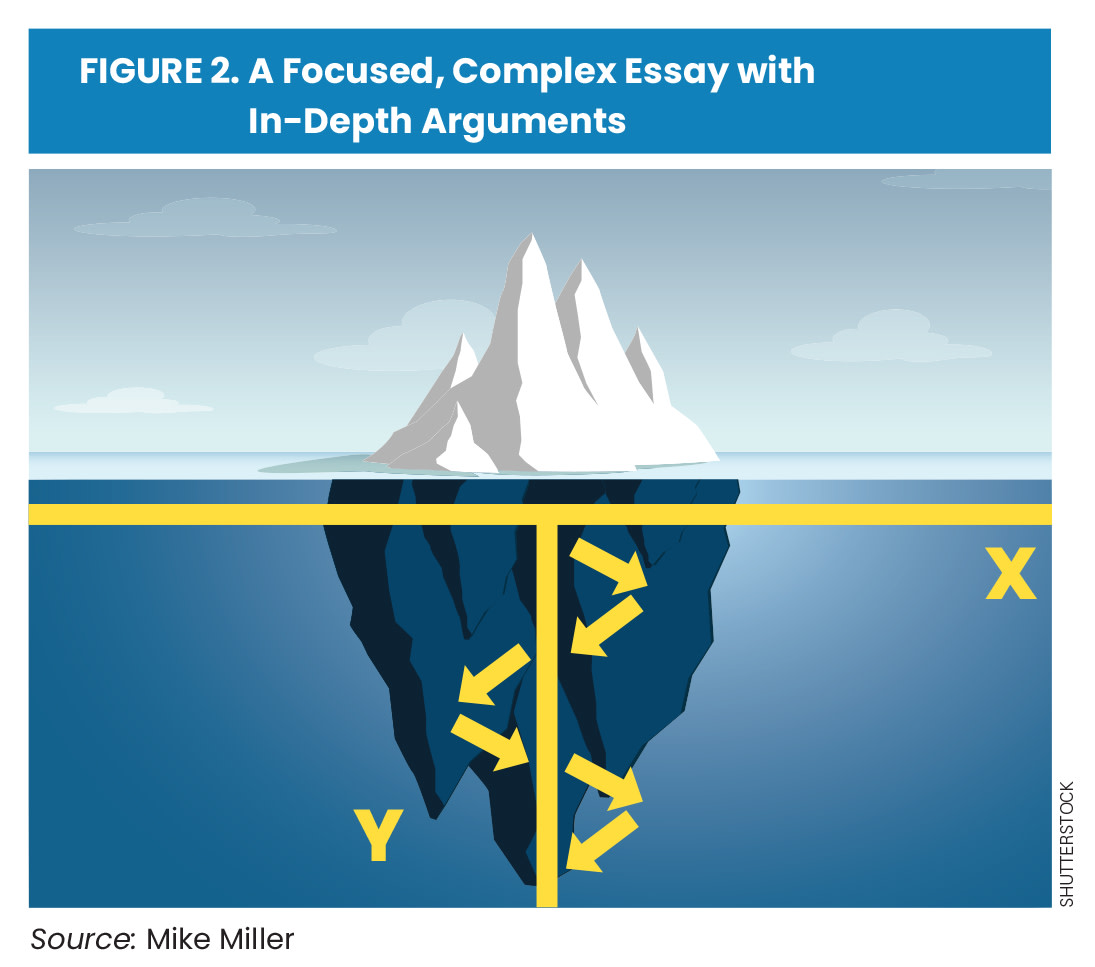

Ella's second draft more closely resembles Figure 2. Rather than skimming along the X axis, writing about several topics superficially, Ella pursues one in depth, relentlessly driving down the Y axis. Her topic sentences reflect a continual sense of focus and show she is genuinely addressing counterarguments. For example:

Although Belle is a "smart and open minded" princess, the subject of her book adds tension to her validity as a feminist role model.

Belle's choice in books imprisons her in yet another gender stereotype and inhibits her critical thinking and growth.

The fact that Belle's book is a fantasy novel is not entirely bad or good.

The romance aspect of the novel, unfortunately, decreases Belle's validity as a truly feminist role model.

Words like book, books, and novel signal that Ella is continually focused on the subject of Belle's reading.

This improved focus allows Ella time and space to complicate her argument. For example, Ella demonstrates that Belle is a voracious reader, a quality that makes her a worthy role model for adolescent girls. "But, upon closer inspection," Ella writes, "Belle's reading sends mixed messages to viewers. Why does a teenage girl read the same romance novel over again and again? Why doesn't she read books that spark her critical thinking in addition to her imagination?"

It might be closer to the truth to say that an increased focus forced Ella to deal with complications and counterarguments, what Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein (2014) call "naysayers":

If you fail to plant a naysayer in your text, you may find that you have very little to say. Our own students often say that entertaining counterarguments makes it easier to generate enough text to meet their assignment's page-length requirements. (p. 80)

We can help students understand that, with greater focus, their subject can become a representative example of a larger concept.

Some students bring up multiple topics in their writing because they fear they won't be able to sustain a longer piece of writing about one specific subject. To counter that fear, we can help students understand that, with greater focus, their subject can become a representative example (Rosenwasser & Stephen, 2011) of a larger concept. Belle as a reader, for example, serves not only as a representative example of Disney princesses, but also of young female readers. Ella's revised draft expanded to draw from research not only on Belle's reading specifically, but also on gender roles, cartoons, Disney animated films, literacy, feminism, and the intersections between and among those fields. She was able to touch upon disparate fields, but only as they related to her focused topic, to which she continually returned, as per the direction of the arrows in Figure 2.

Ultimately, Ella's increased focus and willingness to complicate her argument led her to a more complex understanding of her subject:

Before examining the film deeply, I was convinced that Belle was unquestionably the best princess role model. But, through my research, I began to notice subtle details about Belle's personality that I had not in all of my previous times seeing the film. Now, it troubles me that my favorite princess is not reading Shakespeare or the works of ancient Greek philosophers or helping her father with his engineering creations. Although I admire her determination to continue reading in spite of the jeers of her fellow villagers, I would have wished to see her reading something other than the same fantasy-romance novel for the third time.

It's telling that Ella uses the adverb deeply: her focused, in-depth writing and thinking has led her beyond superficiality and simplicity into a different kind of knowing, one more comfortable with complexity.

Beyond the Shallows

In the introduction to this article, I referenced a prompt about cellphones. They, like laptop computers, are double-edged swords of productivity and distraction in the classroom. In his aptly named book The Shallows, Nicholas Carr decries the internet's effect on thought: "When the brain is overloaded by stimuli, as it usually is when we are peering into a network-connected computer screen, attention splinters, thinking becomes superficial, and memory suffers. We become less reflective and more impulsive" (2020).

My job as a teacher is to encourage students to leave the safety of shallow intellectual waters for the more difficult, but ultimately more rewarding, depth of complexity.

My job as a teacher is to counter shallow thinking, to encourage students to leave the safety of shallow intellectual waters for the more difficult, but ultimately more rewarding, depth of complexity. While we shouldn't supply our students with ideas, we can help them to focus on their best ones. There have been times during class discussions and writing conferences where I have said, "I don't mean to complicate things for you, but …" before correcting myself: "No, wait; I do mean to complicate things for you. That's my job."