The pressure for fast-paced learning is perhaps one of the greatest obstacles to leveraging opportunities to learn in ways that will stick with our students. At the core of the problem is our contemporary culture of speed: The immediacy of an Amazon delivery; the instant hit of dopamine from scrolling through social media; the pressure to respond multiple times in a single class discussion. Challenging this need for speed can be daunting. But if we want to prepare learners with a foundation for thinking and learning, we have to embrace a slower pace that allows us to explore ideas iteratively and for extended periods of time. In education, a helpful idea lies in the classical adage festina lente—to make haste, go slowly (Krahenbuhl, 2020).

Researchers and practitioners alike recognize that deeper learning—"the process of learning for transfer"—is the ultimate aim for successful outcomes (Barseghian, 2012), and many evaluation instruments for instruction prioritize the "depth" and quality of the questions educators ask. Yet in the rush to "go deep," it is all too easy to undervalue the essential role that "shallow" understanding plays in students' capacity to explore and understand content more fully. Shallow understanding, when students have some understanding of the material, is a necessary precursor to deeper understanding. Research has consistently shown that most of the learning gaps between groups of students in our school systems can be winnowed down to one type of gap: knowledge gaps (Hirsch, 2016; Wexler, 2019; Wiliam, 2018). If we want to reduce these gaps and improve learning, it would be worthwhile to spend some more time building foundational knowledge.

The Devaluation of Shallow Understanding

In general, educators today have a tendency to rush past shallow understanding (think level 1 activities in Webb's DOK framework). This tendency, however, burdens our efforts to dive deeper into understanding because of a misconception. Most educators will readily affirm that basic factual knowledge matters, but they also acknowledge that it is not their end point. Our pursuit to go deeper as quickly as possible has created a stigma around spending time on simple factual recall and knowledge-building types of questions. For example, if my evaluation requires students to be engaged in higher-order thinking, I might justify skipping over asking the class lower-order questions.

Many teachers, through no fault of their own, feel obliged to go quickly through foundations when perhaps it might be advantageous to provide additional practice time.

These decisions are largely byproducts of living in an environment in which we grapple with a tension between immediacy and focusing on what is most important. Many teachers, through no fault of their own, feel obliged to go quickly through foundations when perhaps it might be advantageous to provide additional practice time. So, let's explore several strategies that educators can employ to build a better foundation for thinking and learning—one that doesn't bypass the shallow end of the learning pool.

Strategies While in the Shallows

Let's begin by considering a simple reframing of shallow understanding. This is important because there is widely documented research on how the way we frame things changes our perceptions of them, called framing effects (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). First impressions matter: We tend to "rely too heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic," as a result of a phenomenon known as "anchoring bias" (The Decision Lab, n.d.). Simply put, if teachers go through topics too quickly, students will be more likely to anchor their knowledge to underdeveloped ideas.

So, the first strategy I'll discuss is really a meta-level one that can help us recapture the value of shallow understanding. By reframing shallow understanding as essential, we will be less likely to skip over it and more likely to guarantee time for its development.

Strategy #1: Reframe Factual Knowledge as Essential, Not Trivial

Rather than considering basic understanding as "shallow," reframe how you think and talk about it: Basic factual knowledge is not "lower-order" knowledge, but rather "essential-order" knowledge. For students to grapple with "higher-order" knowledge, they must have a sound foundation in place. Shallow understanding is an antecedent—and an essential one—to deeper learning. If we go too deeply too quickly, we run the risk of setting novices up for unintended difficulties.

There's something to the phrase, we measure what we treasure. If we treasure deeper learning, we need to measure antecedents that lead toward that end. How can teachers assess students' readiness for more complex thinking? A simple pretest is one option. Newman and DeCaro (2019) have noted that "combining a pretest with guidance prior to more direct instruction may benefit learning via both metacognitive and cognitive mechanisms" (p. 61). This doesn't mean that any actual grade has to be assigned to pretests, but that teachers should at least commit to checking for shallow understanding.

Strategy #2: Try Retrieval Practice!

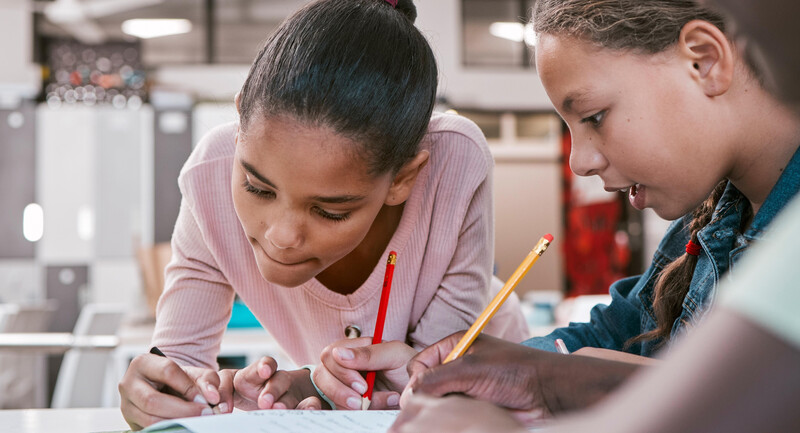

One of the single most attested-to strategies for building essential knowledge and ensuring long-term transfer is retrieval practice (Karpicke, 2012). Retrieval practice can take on many forms, but it always involves students pulling information out of their minds. For instance, a teacher might start class with a quick Q&A, asking students a fact-based question and having them independently record their answers on a white board before sharing them aloud. Another strategy is having students review essential concepts and ideas with flash cards. Other common retrieval practice activities include "brain dumps" (having students write down everything they know about a topic in one minute) and "two things" (having them brainstorm then write down two things they know about a topic or that they learned the day before) (Agarwal, 2018).

We want our students to own an understanding of key information so that learning endures and is theirs to use and apply.

These sorts of on-the-spot formative assessments give learners much-needed practice in retrieving foundational knowledge. We want our students to own an understanding of key information so that learning endures and is theirs to use and apply. For instance, if a teacher asks a student to "multiply 12x12" and she instantly responds "144," she owns that knowledge.

Strategy #3: Make Time for Contemplation and "What If" Thinking

We began with a meta-level strategy to reframe our thinking about shallow understanding. Next, we provided an evidence-based practice to firm up students' understanding of a topic. Now, let's turn to the third step, which allows our learners to wade in the shallow end of understanding just a while longer. In effect, this strategy—a marriage of breadth and depth—involves two steps: (1) requiring students to think about the foundational knowledge they have learned and are learning, and (2) encouraging students to imagine possibilities of what is currently known.

"What if?" is one of the most provocative questions we can ask our students. However, "what if" operates from a fundamental assumption—namely that you know what is, in order to imagine what could be. In other words, "we must know before we challenge the status quo" (Carter & Krahenbuhl, 2022). By drawing on the first two strategies—ensuring time for and providing practice of foundational, shallow knowledge—we lay the groundwork for challenging students to wade deeper into the content. That involves explicit consideration of the ideas they currently understand and reflecting on what is (current knowledge) and what could be (critical analysis).

Beyond "what if," we can also invite our students to contemplate the implications of knowing. For instance, imagine your students understand the second law of thermodynamics to be that in all energy exchanges, if no energy enters or leaves the system, the potential energy of the state will always be less than that of the initial state. Invite them to ponder their understanding of the law: "What does this mean for a tub filled with hot water?" Or zoom out to a macro level for high schoolers, asking, "What does this mean for the universe?" Allowing students to think through what they know, at the shallow level, will prod them toward the deep end—at a pace that works.

The Foundation of Effective Thinking and Discussion

By leveraging these three strategies, educators can cultivate an environment in which a sound foundation of shallow understanding is established, allowing for richer and more flexible thinking. This all begins with the courage to slow down in the midst of a fast-paced world.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ Does your school or district's curricula feel too crowded or overloaded? If so, how do you (or your teachers) navigate the pressure to teach a lot in a short timeframe?

➛ Think about a time you sped through a lesson but realized, too late, that students didn’t have a grasp of the basics. What could have been done differently?

➛ Is retrieval practice a regular tool in your teaching toolbox? If not, how might you incorporate a one-minute activity in tomorrow’s lesson?