Who dares to teach must never cease to learn.—John Cotton Dana

The world is rich with learning opportunities, especially for educators. Teachers can learn from video recordings of their lessons, instructional coaching, conversations with their principals and peers, formative assessment and other data, and student feedback. Similarly, principals can learn from 360-degree feedback; video recordings of meetings they lead or presentations they give; conversations with teachers and students; and data on achievement, school climate, or teacher satisfaction, such as from Gallup's Q12 Engagement Survey (Gallup, 2016).

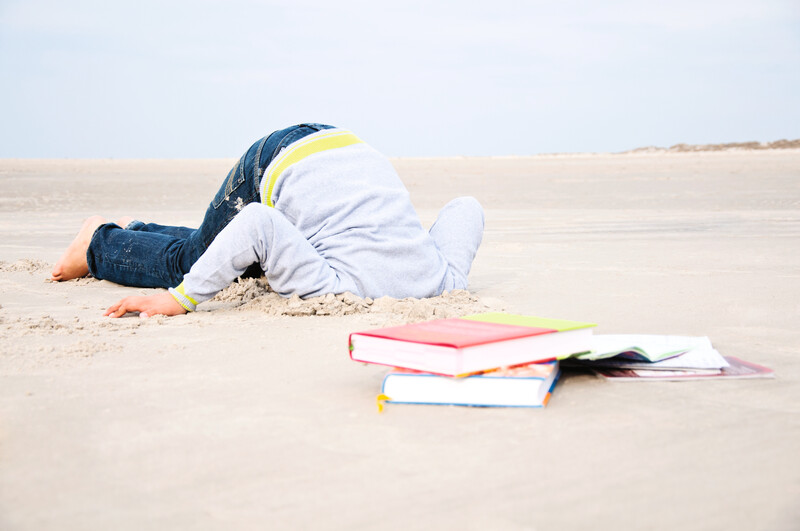

We know that learning is essential for professional success, self-efficacy, healthy relationships, and well-being. However, when opportunities to learn present themselves, we frequently turn away. Offered the chance to learn, we choose instead to move into what I call the Zero-Learning Zone.

What is the Zero-Learning Zone?

We step into the Zero-Learning Zone whenever we act, consciously or unconsciously, in ways that block our own learning. For example, we might be shy about how we appear on camera and therefore turn down the chance to learn from video recordings of a lesson. We might say no to an opportunity to work with a coach; dismiss feedback from a colleague, principal, or student; adopt beliefs that isolate us from new ideas; blame others; or make excuses that shift responsibility away from ourselves and onto someone else. There are many reasons why we take a pass on an opportunity to learn, but before we explore how to get out of the Zero-Learning Zone, we have to take a look how we get there in the first place.

Blindspots. We often miss the chance to learn because we do not see that we need to learn. James Prochaska, an expert on the personal experience of change, and colleagues identified the first stage of change as pre-contemplation—not realizing we need to learn so that we can change our situations (Prochaska, Norcross, & DiClimente, 1994). Because of perceptual errors such as confirmation bias, habituation, stereotypes, primacy effect, and recency effect, we don't see reality clearly. As researcher and social psychologist Heidi Grant Halvorson has written in No One Understands You and What to Do About It (2015), "The uncomfortable truth is that most of us … can't see ourselves truly objectively" (p. 4). A principal, for example, might not see how much time he wastes on unimportant issues during staff meetings until he watches a video recording of a meeting.

We don't think the learning is worth it. Two factors need to be in place for us to grow and change (Patterson et. al, 2008). First, we need to believe we can do what we are considering. Second, we need to believe that what we are considering is worth the effort. If either factor is missing, we are much less likely to embrace the opportunity to learn or change. Teachers who are introduced to new teaching practices may forgo implementation because they can't see the practice as working or because they can't see themselves mastering the new strategy.

Identity. Our deepest learning experiences usually challenge us to re-think "the stories we tell ourselves about who we are" (Stone & Heen, 2015, p. 23) and reconsider what kind of people we are, our efficacy, ethics, and overall place in the world. But we are resistant to any experience that causes us to re-evaluate what we think to be true about ourselves. It's much easier to just say no. "Learning about ourselves can be painful—sometimes brutally so," write Stone and Heen, "and the feedback is often delivered with a forehead-slapping lack of awareness for what makes people tick. It can feel less like a 'gift of learning' and more like a colonoscopy" (p. 7).

Hope (or, more precisely, its absence). Gallup Senior Researcher Shane Lopez (2013) summarizes a three-part process for hope, first identified by University of Kansas researcher Rick Snyder. To have hope we need goals, "pictures of the future [that] identify an idea of where we want to go, what we want to accomplish, who we want to be" (p. 24). Second, hope involves agency, our belief that we have control over our lives and that we can meet our goals. Finally, we need to have multiple ways of getting to the goal. Lopez suggests that when we lose hope, it is often because we lack one or more of these three factors. And when people do not have hope, the easiest place to go is the Zero-Learning Zone.

Fear. When I discussed the Zero-Learning Zone with colleagues, a word I heard frequently was fear. We might be afraid that we are going to embarrass ourselves or fail. This emotion also overlaps with the other Zero-Learning Zone factors. For example, we may fear the unknown impact that learning might have on our identity. A loss of self-efficacy. Confronting our own hopelessness and blind spots. You get the idea.

A well-known education researcher told me that he believes fear blocks learning when people embrace a partial answer to a challenge or problem, creating the illusion of a comprehensive solution. That "solution" can become so entwined with our identity that we seek out proof that our ideas work, rather than information that would help us learn. A partial, if flawed, solution can feel better than risk or uncertainty. But real learning only occurs when we confront our fears and move forward.

Getting Past Zero

Given the complexity of learning and our own flawed perceptions of ourselves, we shouldn't be surprised if we find ourselves in the Zero-Learning Zone. Ron Heifetz captured our predicament well in his book (with Marty Linsky) Leadership on the Line (2002) when he wrote about adaptive change, a particular form of deep learning:

Adaptive change stimulates resistance because it challenges people's habits, beliefs, and values. It asks them to take a loss, experience uncertainty, and even express disloyalty to people and cultures. Because adaptive change forces people to question and perhaps redefine aspects of their identity, it also challenges their sense of competence. Loss, disloyalty, and feeling incompetent: That's a lot to ask. No wonder people resist. (p. 30)

But while learning is challenging, perhaps even threatening, it is also essential. To live truly fulfilling lives, we need to be curious. Choosing not to learn is choosing intellectual impoverishment, something teachers cannot afford. Teaching is a learning profession, in part because each individual child is a unique learning opportunity, and also because to ensure students receive the learning they need and deserve, we need to keep striving to be better. What's more, if we expect our students to learn, we need to show that that we are learning.

Fortunately, there are many things we can do to move out of the Zero-Learning Zone. Here are a few:

Flip your perspective. One way to move forward as a learner is to gain a different perspective on how you lead and teach, or how your students learn. The easiest way to do this is to video record yourself doing something important, such as teaching a lesson. If you're not ready for video, try the audio record function on your phone. Interview students to hear their perspectives on your teaching. This will force you to see or hear things outside of your own perspective and, yes, learn.

When we act to get a different perspective on our actions, by looking at video or interviewing students, for example, we are intentionally stepping outside the Zero-Learning Zone. It takes courage to choose to learn, and real learning requires a real picture of reality that comes from flipping our perspective.

Create specific goals. Well-crafted goals can provide guideposts that nudge you out of your comfort zone. As Heidi Grant Halvorson (2012) says, "Taking the time to get specific and spell out exactly what you want to achieve removes the possibility of settling for less—of telling yourself that what you've done is good enough. It also makes the course of action you need to take much clearer" (p. 6). Our research on coaching at the Kansas Coaching Project at the University of Kansas identified five variables that make for effective goals. We summarize these variables as PEERS goals: Powerful, Easy to Achieve, Emotionally Compelling, Reachable and Student-Focused. Most frequently, the PEERS goals that teachers set are achievement-related (students can write a well-organized paragraph), engagement goals (students demonstrate that they have hope on weekly quick, informal assessments of their attitude), or behavior goals (transition time takes up less than 5 percent of class time).

Utilize design thinking. Design thinking is a methodology for creating and problem solving that applies the strategies of design to real-world challenges and opportunities. A teacher who applies design thinking to achieve a goal in her classroom might, for example, decide that she wants a higher level of engaged conversation during classroom dialogue. Taking the stance of a designer, she might identify the goal to be that 75 percent of students contribute high-level comments during classroom dialogue; try out and adapt various approaches to facilitating discussion, such as encouraging more active listening, using different questions or more provocative and relevant thinking prompts, providing more affirmation of students, or establishing clearly defined academic-discussion norms; gather data each time she tries out a different approach; make modifications based on the data; and continue to test and adapt until the goal is met.

One of the advantages of design thinking is that it reduces the stress and anxiety of attempting change without a framework, and therefore helps to push teachers out of the Zero-Learning Zone. Rather than trying to get things perfect the first time, teachers taking the design approach experiment, gather data (possibly through video), try again, and repeat, learning all the time.

Conduct a hope audit. As mentioned earlier, the three factors that are essential for hope are agency, goals, and pathways to the goals (Lopez, 2013). If we feel that we may be losing hope, we may find it useful to conduct an audit to see if we are coming up empty in one of those three areas. Ask yourself: Do I have a clear, specific goal? Do I have strategies I can use to hit the goal? Do I believe I can hit the goal? If your answer to any of these questions is "no," then you need to identify resources that can help you find hope and reach that goal.

A teacher who is starting to lose hope that all of his students will learn to write a well-organized paragraph can conduct a hope audit by first considering the goal: Has he clearly stated what a well-organized paragraph looks like? If not, perhaps he could create a checklist for what an effective paragraph should look like. Next, he could look at pathways: What strategies could he use to increase student success? Maybe he could have students self-assess their writing, work with partners, or look at more examples. Or the teacher could do more modeling or provide better feedback. Finally, he must consider agency: After implementing these changes, does he believe his students can improve? If not, what different strategies or goal adjustments need to change?

Keep it simple and targeted. Learning may seem overwhelming if we try to accomplish too much all at once. Choose one learning target and stick with it until it is accomplished. An excellent example of targeted learning was described on the now-defunct Teach TV web site in the United Kingdom. The video showed an elementary teacher explaining how each Friday she made a list of all the students in her class. For the students whose names she forgot or had to struggle to remember, she made notes about their unique strengths. The next week she took special care to think about the students she'd forgotten and reminded them and herself of their strengths so that she didn't forget those students the next Friday.

Treat yourself with compassion. Teachers are often harder on themselves than anyone else would ever be, and certainly harder on themselves than they would ever consider being with a friend. I believe educators need to be more compassionate toward themselves. Daniel Pink (2018) offers a simple way for doing that. He suggests that when we are disappointed by something we've done, we should write ourselves an email expressing compassion or understanding, imagining "what someone one who cares about you might say" (p. 143). When we step out of the Zero-Learning Zone we will have times when we screw up or experience fear. To keep learning, we need to adopt what Pink refers to as a "the converse corollary of the Golden Rule: … to treat [ourselves] as [we] would others" (p. 143).

Leading Our Own Learning

Teacher-led learning has great potential because we can influence and inspire students when we model our own learning. When we improve, we have greater impact on students' achievement and well-being. Additionally, when we lead our own learning, when we see more and learn how to act more effectively, our lives improve. Learning is our lifeblood, and we live better when we learn more.

To experience that learning, however, we need to step outside of the Zero-Learning Zone. We need to demonstrate the courage it takes to watch ourselves on video, interview students, experiment with prototypes and iterations, stay hopeful, draw on the resources that already exist, and forgive ourselves when things don't work out. What matters is that we intentionally keep learning. When we do, our children's lives will be better, and so will our own.

Guiding Questions

› Have you ever found yourself in the Zero-Learning Zone? What do you think was the cause of your stalled learning?

› What is one topic or subject that you'd like to learn more about? What steps can you take today to find out more about it?

› What opportunities can you and your colleagues take advantage of to see yourself and your teaching from a different perspective?