Recently, a school administrator approached a colleague and me for support in addressing anti-Black racism and bias on their campus. As was happening at many independent schools, this school’s Black students, teachers, and alumni had developed a Black@ Instagram page to share their experiences of racism. The leadership team organized various responses to this issue of racism at the school, from parent meetups to student affinity groups to faculty trainings. Now they wanted us to conduct a curriculum audit “through a DEI lens.”

Looking deeply at the curriculum—as opposed to adding another speaker, book group, or student club with no systemic engagement—is a positive and necessary step in dismantling bias. Still, I wondered what the leadership team truly wanted. Schools and other organizations often use the initials DEI to refer to diversity, equity, and inclusion as if they were a single concept. But these words have distinct meanings. In an essay for Inside Higher Ed, scholar D. L. Stewart (2017) explains that “diversity and inclusion rhetoric asks fundamentally different questions and is concerned with fundamentally different issues than efforts seeking equity and justice.” He notes:

Diversity asks, “How many more of [pick any minoritized identity] group do we have this year than last?” Equity responds, “What conditions have we created that maintain certain groups as the perpetual majority here?” Inclusion asks, “Is this environment safe for everyone to feel like they belong?” Justice challenges, “Whose safety is being sacrificed and minimized to allow others to be comfortable maintaining dehumanizing views?”

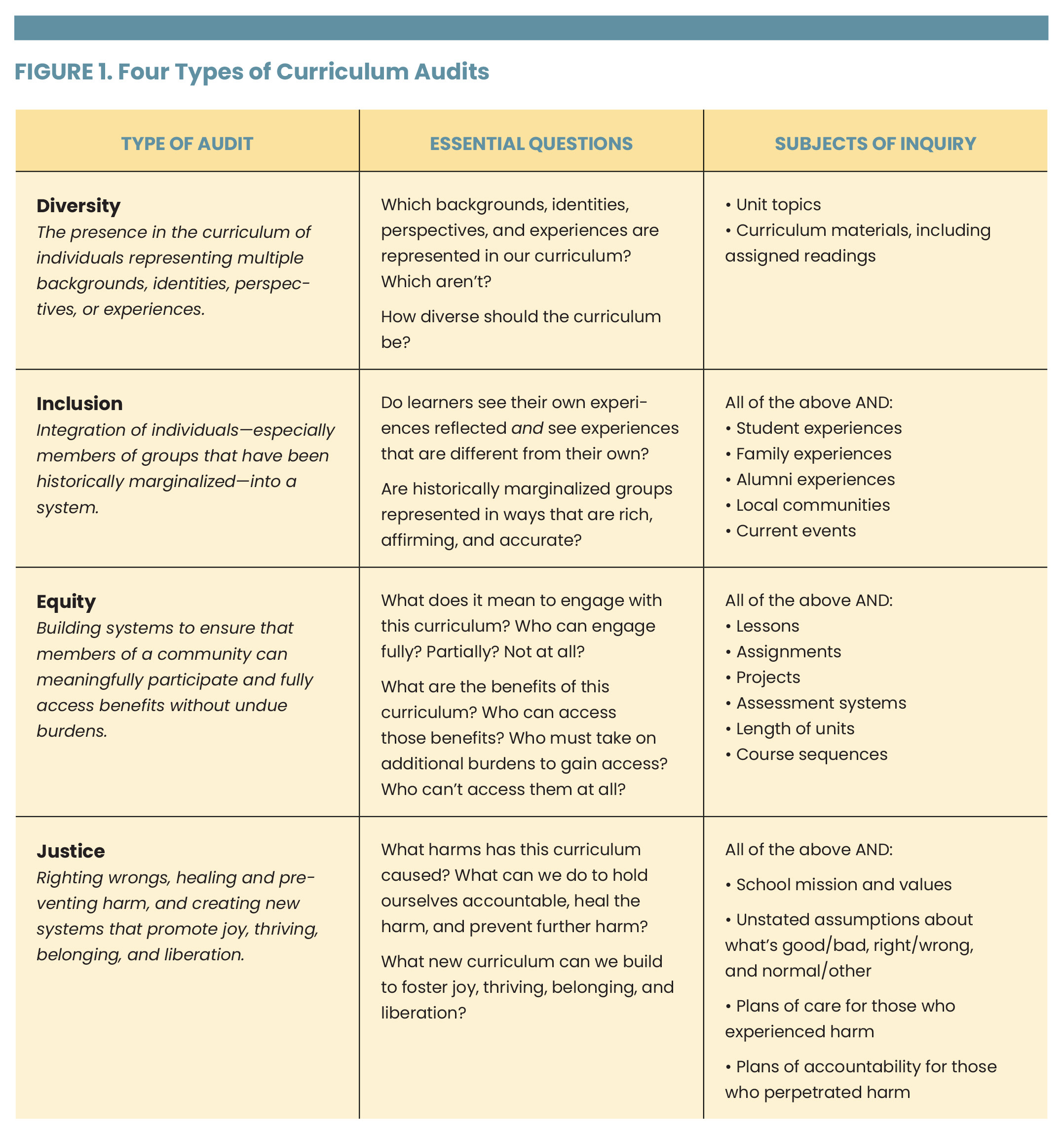

If diversity, inclusion, equity, and justice are fundamentally different ideas, then it’s less useful to think of auditing the curriculum “through a DEI lens” than to consider four distinct kinds of curriculum audits schools might conduct: diversity audits, inclusion audits, equity audits, and justice audits. Figure 1, derived from my work in schools, summarizes characteristics of each kind of audit.

1. The Diversity Audit

Diversity is the presence of individuals representing multiple backgrounds, identities, perspectives, or experiences within a group. In a diversity audit, we ask which backgrounds, identities, perspectives, or experiences are represented in the curriculum (and the usually unspoken corollary: which won’t be).

We also ask how diverse the curriculum should be. “Diversity” in curriculum and materials is a matter of degree. For example, when I was in 10th grade, my English class read canonical texts by white males until the last book of the year, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. In a Women and Literature elective I took my senior year, our teacher chose one book by an Indigenous woman, one by a Latina woman, one by a Black woman, and one by an Asian-American woman, and had us each choose a fifth book by any woman. This curriculum was more diverse than my 10th grade one, yet we still read no stories by or about trans women, lesbians, or Jewish, Muslim, or disabled women—unless we chose to for our fifth book.

Increasing diversity in materials, while worthwhile, usually preserves existing power structures, because someone—usually a someone with historical authority—decides which groups are represented and the extent of that representation. Conducting a diversity audit is also fairly straightforward: We list the topics we teach and resources we use, ask ourselves if our lists have as much variety as we want to see, and make some adjustments. Such audits often don’t require systemic change.

2. The Inclusion Audit

Inclusion is the integration of individuals—especially members of historically marginalized groups—into a system. To borrow a metaphor from Rudine Sims Bishop (1990), inclusion audits ask whether the learners at the school see “mirrors” reflecting their own experiences and “windows” into experiences that are different from their own.

Getting the “mirror” part right requires conversations with students, families, and alumni, to listen for how they experience the curriculum and what being included would look like for them. For instance, at my former school, a group of Asian-American students protested the lack of books with Asian characters. The 8th grade English team added Jean Kwok’s Girl in Translation to the summer reading list. It’s a beautiful story, but I wondered—did our AAPI students, all of whom were American-born and most of whom came from wealthy or middle-class families, relate to an immigrant character who works in a sweatshop?

A full inclusion audit involves exploring local environments and current events to contextualize the curriculum for your particular set of learners, in their particular place and time. When I was in elementary school, learning about local spaces amounted to occasional trips to a park or museum. The older we got, the less we left the classroom, and “studying current events” meant bringing in articles clipped from newspapers, summarizing them, then returning to whatever we were studying. Real inclusion would contextualize the learning for example by conducting field studies, interviewing community members, reading local history, and perhaps most important, by looking for larger patterns or questions that both a local or current event and the curricular unit connect to.

Inclusion audits ask whether the learners at the school see “mirrors” reflecting their own experiences and “windows” into experiences that are different from their own.

Inclusion audits also ask whether marginalized groups are represented in rich, affirming, accurate ways—as opposed to through incomplete or distorted views (such as if students read one book with an Asian character and learned about Chinese transcontinental railroad workers in history class, with no other AAPI representation in learning throughout high school). Inclusive curricula offer full-length mirrors of students’ own experiences and wide windows into unfamiliar ones. Like diversity, of course, inclusion is a matter of degree.

Finally, an inclusion audit examines whether most students are passive recipients of the curriculum or active contributors to it. By looking at the ways students encounter and respond to course material, educators can gauge whether their practices only ask students to receive information someone else discovered, assembled, or created, or also have students discover, assemble, and create knowledge themselves.

3. The Equity Audit

Ultimately, diversity and inclusion audits ask what the curriculum has, while equity and justice audits ask what the curriculum does. Equity means building systems to ensure that members of a community can meaningfully engage and fully access benefits without undue burdens. An equity audit involves discovering what it means to engage with the curriculum—and what its benefits are—then asking, who can engage fully? Who can engage only partially—or must hide, diminish, or change some part of themselves to engage? Who can’t engage at all? Who can easily access the curriculum’s benefits and who must take on additional burdens to do so?

Inequitable access can be hard to spot. Imagine a 4th grade class is studying multiplication and division, and the teacher figures anything is better with food. She tells her students to have their parents write down a family recipe that reflects their cultural heritage. The students will figure out quantities for 2, 6, and 25 people (the size of their class). For bonus credit, students can make the food and bring it to school to share. This sounds like a fun assignment, and the teacher might intend to be culturally inclusive by asking for a heritage recipe. However, multiethnic students might feel the need to choose between heritages, adopted students might not know what a heritage recipe means for them, and students who don’t live with a parent might wonder if it’s OK to ask their caregiver for a recipe. Students living with food insecurity might become anxious and hesitate to ask for a recipe. While some students can easily cook the dish with an available adult, kids whose caregivers work long hours might not be able to cook by themselves or afford ingredients to feed 25 people. Students’ food allergies and religious dietary codes might prevent some kids from fully engaging.

I can almost hear a past version of me becoming defensive: “Is it better to just assign math worksheets that are equally accessible and make the kids equally miserable?” Of course we should create assignments that engage students, and equity demands that we examine what engagement entails and whether all students can fully engage. After an equity audit, this 4th grade math teacher might change her project to have her students ask any significant adult about a food memory, find a recipe online that relates to the story, and use multiplication and division to adjust the quantities. Or she could work with caregivers to design choices for the assignment that would be meaningful and culturally sustaining for each student.

Beyond lessons and units, an equity audit means examining the courses and programs in which they’re embedded. Are there advanced classes? What is “advanced” code for? What criteria determine who gains access to these classes, whose criteria are they, and which students tend to meet them? For example, at my older child’s high school, “advanced” biology students move faster and memorize more material, while “regular” biology students have a more inquiry-driven and project-based curriculum. Who decided that advanced means having more time to read and more capacity to remember? Whose needs does that serve, and who gets left behind? An equity audit addresses questions like these.

Finally, an equity audit involves examining who benefits from the curriculum and who has access to those benefits. After successfully learning about multiplication, or reading Girl in Translation, for instance, what will students be able to do next? Where and how do we imagine them using the knowledge and skills we teach? Do we provide opportunities for all students to use what they learn in school to discover themselves, relate to others, and strengthen their communities?

4. The Justice Audit

Justice means righting wrongs, healing, and preventing harm, and creating new systems that promote joy, thriving, belonging, and liberation. In a justice audit, we ask, What harms has this curriculum caused? What can we do to hold ourselves accountable, heal the harm, and prevent further harm? What new curriculum can we create together that promotes joy, thriving, belonging, and liberation?

As a Jewish child attending a Jewish day school, I experienced such a curriculum. At our yearly Passover seder, everyone played a part in telling, singing, dancing, and eating the Exodus story. Another yearly ritual brought the entire K–8 community together to learn about the Shoah. In a gym lit by 600 candles that represented the six million murdered Jews, we sang Ani ma’amin be’emunah shelemah b’viyat Ha’Mashiach, Hebrew words uttered by our people on the verge of death in a last expression of faith and resistance.

Not everyone has such respectful, affirming experiences at school. According to Paul Gorski (2020), founder of the Equity Literacy Institute, some schools say they’re trauma-informed without examining how their own policies and practices sometimes cause trauma. Education professor Stephanie Jones (2020) shares that her teacher had students pick cotton to experience what life was like for people who were enslaved. Jones calls this kind of insensitive assignment that can harm students psychologically curriculum violence (Ighabor & Wiggan, 2010). Professor and writer Bettina Love (2019) uses the term “spirit-murdering” to describe how education systems and structures—including curriculum—can harm Black children.

Some educators balk at language like trauma, violence, and spirit-murdering, saying it’s too extreme to describe curriculum. In my experience, these are usually white cisgender teachers and administrators who haven’t examined how their own privilege informs their practices. A justice audit necessarily involves educators in positions of societal and institutional power asking hard questions, confronting painful truths about themselves and their work, and giving up cherished practices—so we can build a curriculum that heals and uplifts.

Because justice audits involve uncovering harm, they can’t involve only naming the harm and replacing harmful practices. They must also involve a plan of care for those who’ve experienced harm and a plan of accountability for those who have caused it. If a justice audit uncovers anti-Blackness and transphobia in the curriculum, for instance, a plan of care must center Black and trans students. A good plan includes opportunities for safety and support in the short term, empowerment in the medium term, and systemic change (in and beyond the curriculum) in the long term. A plan of accountability means educators and leaders must confront any biases they have about specific groups and how those biases manifest at school—and use cognitive and pedagogical tools to prevent any bias from harming students.

A justice audit is the most challenging because of the pain it unearths. Educators cannot do this work on their own; a justice audit must be communal, with support from mental health and justice experts, and ideally led by community members in historically marginalized groups. Shifting away from hierarchical leadership and compartmentalized practice will defy norms in many institutions.

Choosing a Type of Audit

Each type of audit requires a distinct set of skills and tools. For a diversity audit, you’ll only need to know how to make a basic curriculum map and chart out unit topics and resources, then count up which ones reflect particular groups. Inclusion audits take longer. You’ll need to conduct focus groups to ask students, parents, and alumni about their experiences, then compile your findings and look for patterns. You’ll also need to explore the local community and recall recent events to see how students’ here and now are reflected in the curriculum—or aren’t. Your faculty might be able to do this themselves, but bringing in outside observers can widen your lens. Any insider has a stake in the curriculum and might have trouble seeing problems.

For an equity audit, you’ll need to do all of the above plus map out the curriculum in a more detailed way. You can’t just tally up who’s present or missing; you’ll need to look at how long students spend studying any given topic, how they receive and construct knowledge, which perspectives and worldviews matter, the kinds of work products students create, and how they’re assessed. This is a much bigger project that involves quite a lot of work. Hiring consultants means paying for their services; asking teachers to self-assess honestly and observe one another requires trust. You can cultivate that trust during the process itself, but it takes time.

To do a justice audit, you need to do all of the above and develop a plan of care for those who’ve been harmed, and some way for those in power to hold themselves accountable for ways they’ve misused that power. This will likely invoke defensiveness and denial from some. I must say, I’ve never actually seen a whole school do a justice audit, but I’ve seen individual teachers or small groups reckon with their curricula in this way—and they often experience tremendous stress. I know many excellent educators who’ve quit their jobs rather than continue to face white rage when they tried to teach a just curriculum, and other teachers, myself included, who retreated from curricular battles so we could live to fight another day.

Many schools say they want to do a curriculum audit “through a DEI lens,” but really mean doing a diversity or inclusion audit—both because equity and justice audits require much more time and effort and because people in privileged positions are reluctant to confront how they feel when they realize what the curriculum does to some students.

If your school wants to do an audit to make its curriculum more equitable and just, you’ll need to ponder certain values questions, such as, Do we just want to adopt a more diverse and inclusive curriculum and then move on? Or are we ready to see any harms we’ve caused and hold ourselves accountable? The ultimate question might be, Are we ready to make our students’ lives more important than our own comfort?

The PD Curator

Empower teachers and students alike.