Like schools across the county, mine faced major challenges in the spring of 2021. Many of our students were still learning remotely and we had a larger than normal population of learners struggling academically, socially, and emotionally.

In the middle of our transition back to in-person classrooms, I learned that in the fall, my department would begin partnering with the local community college to offer two new dual credit composition courses. These courses would be open to any student who demonstrated college reading and writing readiness either through their unweighted GPA, EBRW SAT scores, or by passing a placement test through the community college. Passing the dual credit courses would give students credit at both the high school and the college level, and since teaching the class required a master’s degree in English, there were a limited number of teachers who the college would accept as instructors. One of the English teachers in my department volunteered to teach the first course, Composition I Honors Dual Credit, and I offered to teach the second, Composition II Honors Dual Credit.

I reached out to the program coordinator at the community college for guidance and found out that while the college English Department had a required set of learning objectives, there was no required text and only two required assignments, for which students would research and produce written and multimedia products that addressed social inequalities. The structure and pacing of the course, along with most of the assessments, were up to me.

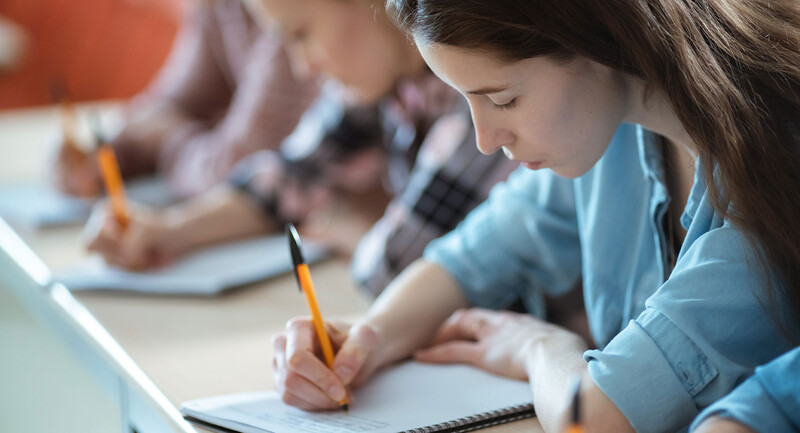

Understanding the dire challenges facing the seniors I taught—and, really, facing all the students at my school—I wanted to create a course that would help students return intellectually and emotionally to the classroom. During remote learning, students became used to completing work on their own terms; they could choose the time and location for their learning. In order to engage students who were not in front of us, educators made many more assessments project-based to build on student interest. As I planned this new course, in which students would learn in person, I knew I wanted to preserve that student choice.

Finding Direction

During the summer of 2020, I read several books on blended learning to help teachers in my department prepare for the following school year. One text, Blended Learning in Action: A Practical Guide Toward Sustainable Change, stuck with me. It argued that student ownership “occurs when the learner actually becomes a self-directing, self-resourcing, self-correcting, and self-reflecting agent in the learning process…[and] as students mature they assume an increasing role in this process” (Tucker, Wycoff, & Green, 2017). I decided that was what I wanted for the senior students: an experience where they made the choices about their learning—and I became a facilitator.

Luckily, my school offers supportive instructional coaches with whom I discussed the idea. First, we brainstormed a list of possible writing-based summative assessments, both traditional essay writing and more nontraditional, or multimodal, writing. Then, we discussed potential topics for students to focus on. Because I wanted to increase student choice, I did not want to dictate the topics that they needed to write about. However, I have found that students flounder without guidance, so I looked for a theme that was timely, engaging, important to the students, and still provided choice. This course would be filled with second semester seniors, ready (or not) to leave the safety of our high school and begin their futures, and that is what they would be thinking about: planning for the future. I then realized I had my theme, or essential question, that would drive our work over the course of the semester: What is the future you envision, and what needs to happen for that vision to become a reality?

With that in mind, one instructional coach and I decided on the summative assessments for the course. Students would be required to write one persuasive essay and one informative essay as required by the community college. Each student would also be required to choose a third piece of writing that could be a letter, an opinion piece (op-ed), or a narrative. In addition, students would be asked to complete two multimodal assignments. They could choose to create a podcast, TED talk, infographic, photo essay, public service announcement, blog, or website. In whatever form students chose to complete the assignment, they would still need their project to answer the essential question of the course. Because students would be completing different assignments that would take varying amounts of time, they would also choose their own composition schedules and due dates. They would, in other words, be true self-directed learners.

Our obligation as educators is to help students find their voice and become independent.

Relationships as a Foundation

At the start of the second semester, in January 2022, 17 students came into my classroom ready to earn college credit. They had all been together during the first semester; I was the newcomer. While I wanted to build a classroom community and get to know the students, I needed to do so in a way that honored the relationships that they had already formed. Therefore, we learned about each other in relation to the topic of their futures. The students journaled about what came to mind when they thought about the future and looked for similarities between the responses. We watched TED talks such as “How Not to Be Ignorant about the World” by Hans and Ola Rosling to not only discuss our perceptions of the current and future states of the world, but also to learn how speakers effectively combine content, structure, voice, and body language to engage an audience. We read nonfiction pieces such as a chapter out of Think Again by Adam Grant to discuss how authors use research, anecdotes, images, and section headings to guide their audience through a topic. These models helped inform the decisions students made with their work throughout the semester.

After two weeks, students proposed independent plans for the semester that included information on the type of project they were seeking to complete and its topic, connection to the essential question, approximate word count, and due date. Their peers and I offered them feedback on their plans and they could revise, if necessary. From that point on, the course was in their hands.

Because of how much freedom students had to direct their learning, I made sure they had a weekly routine so that they knew what to expect and what their responsibilities would be. Every Monday, students would meet in peer review groups. These were unchanging groups of 4-5 students who were a first source of feedback. Since the course followed a blended learning model, Tuesdays and Thursdays were class optional days. Students could choose to attend class or not, but I would be present in the classroom to assist any student who dropped in and for individual writing conferences. I devoted Wednesdays to project work time and additional individual writing conferences with students. On Fridays, students would engage in mini-lessons and review concepts that had proved challenging. For instance, when many students were making errors with quote incorporation, we took a Friday class to discuss one aspect of quote incorporation, punctuating quotes, and then students completed a practice assignment. When students continued to struggle with a skill, I asked them to come in on a Tuesday or Thursday so that we could go over it together.

Students knew what to expect each day, made personal goals and checkpoints based on their calendars, scheduled writing conferences when needed, and made decisions about whether to attend class the extra two days a week. This was a freedom that many of them said they craved, having experienced it during the time of remote learning.

I wanted my senior students to have an experience where they made the choices about their learning, and I became a true facilitator.

Building Independence

During the last week of the semester, each student created a presentation for the entire class putting together their ideas about the future. As a classroom community, we were able to see the similarities and differences between our visions and celebrate each student’s successful journey throughout the semester. The respect and comradery in the group was palpable.

Through one-on-one conversations and becoming familiar with their chosen projects, I have had the opportunity to get to know my students, their hopes for the future, their interests, and their writing skills. I read a student’s letter to his future self about his hopes going into the world as a transgender man, an informative piece about the teaching strategies a student wanted to use when he had his own classroom, a photo essay about the Earth’s changing environment, and an infographic explaining the top ten pharmaceutical companies one student hoped to work for after college. These were topics in which students were highly invested and although I guided them through the process, each student independently chose their journey.

Over the course of the past two years, our students have changed, and their needs in the classroom have changed as well. Our obligation as educators is to help students find their voice and become independent. Creating opportunities to support that process in every classroom will help them thrive within our building and excel as they leave it.