Here's a scenario we observed that is not uncommon in schools: After Alexia's third hallway fight with yet another student, her exasperated assistant principal shakes his head in dismay and suspends her. In the heat of an altercation or even in the regular busyness of a school day, educators feel pressure to manage student behaviors and meet academic achievement goals. This is understandable. But why do we so often think something's wrong with a student (and react accordingly) rather than wonder what happened to her?

At East High School in Rochester, New York, we have started asking questions of ourselves and of our students that get to the heart of our students' lived experiences. We know there are reasons—good reasons—why a child might act out, keep his head on his desk, or refuse to do homework.

A culture of resiliency, safety, and positivity is the focus for staff and students at East High School in Rochester, New York.

We are a collaborative group: a school administrator, an education researcher, and a pediatric researcher. Our connection was forged in 2015 when the University of Rochester received a five-year grant to work with East High School to improve student outcomes. We leveraged this community-based relationship to focus on students' histories and experiences outside of school and address their trauma.

What we saw in students like Alexia led us to examine research on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—traumatic events occurring from birth to age 17. There are 10 ACEs, including five types of maltreatment (physical, verbal, emotional, and sexual abuse and neglect) and five types of family dysfunction (parental separation; living with a family member who has mental illness, substance abuse, or is engaged in criminal behavior; and witnessing violence among adults in the home) (CDC, 2020).

Children who've experienced ACEs sustain harm to their immunological, neurological, emotional, and cognitive systems (Howell & Sanchez, 2011). Damages follow into adulthood, when these young people experience higher rates of alcohol and substance abuse, depression, lung cancer, heart disease, suicide attempts, and early death (Hughes et al., 2017). The more ACEs a child accrues, the more likely they are to suffer from these short- and long-term effects.

East High School scholars head to breakfast at the start of the day.

Reducing the Risk

The child poverty rate in Rochester ranks first in the nation for similarly sized cities. We also rank third for overall poverty (ACT Rochester, 2018). These statistics increase our students' exposure to trauma and reduce their and their families' access to various forms of support. ACEs know no boundaries, but those living in underserved areas are at higher risk (Mersky, Topitzes, & Reynolds, 2013). The implications for our students' futures are worrisome: reduced physical health, mental health, educational and developmental outcomes.

When East High and the University of Rochester began our partnership, we set out to revamp curricula, teacher support, leadership structure, disciplinary policy, and length and structure of the school day. At the center of our transition sat an intention to radically change our culture and to become a place that honestly and effectively serves students. One key benefit of our partnership is access to the university's medical and nursing programs—community partners that became essential in our approach to students sustaining trauma.

Together, we have implemented a program called Promoting Youth Resilience (PYR) to mitigate the negative effects of ACEs. PYR focuses on building positive behaviors among students, rather than reducing negative ones. We rooted PYR in resilience theory, which posits that in order to overcome adversity, one must have or develop internal assets (for example, self-regulation) and external resources (such as peer support) (Zimmerman, 2013). Resilience theory holds that children with good coping skills, who are connected to community supports and who show compassion, gain a sense of control over their futures, mitigating ACEs' effects on them. Encouragingly, resilience skills are teachable.

A Focus on Resilience

To create Promoting Youth Resilience, we broadened East's behavioral health services. The school had already established a school-based health center through an existing relationship with the University of Rochester's School of Nursing. The onsite clinic provided physical and individual mental health services to students, and we expanded it to include a more comprehensive focus on behavioral health.

We designed Promoting Youth Resilience as a long-term (whole school year) group-therapy program for students with multiple ACEs. These clinical services are provided by University of Rochester's Medical Center clinicians (hired specifically for this program), who are supervised by an experienced social worker or guidance counselor from the East health center. Promoting Youth Resilience involves two main components: ACEs screening (to identify at-risk students) and intervention.

We screen students in 6–8th grades in September of each year. Targeting younger grades allows us to impart skills that they can then carry through high school and beyond. Two URMC masters-level clinicians administer this self-reported survey during students' health classes. Those with multiple ACEs are eligible for the program.

Once we've identified students with three or more ACEs, or who were recommended by administration, we form small groups of six to eight students, based on grade, gender, and schedule availability. After they've been assigned to a group, students have the choice to opt-out of the program. Sessions are held weekly for a full class period in a group therapy room in the school. Since the pandemic, we've developed a modified curriculum for use in remote settings and will continue to deliver the program remotely via videoconferencing until it's safe to resume in-person meetings. In an academic year, each student participates in 20 group sessions.

Mindful Intervention

The program is different for each grade level, building on skills and knowledge taught each year, and adjusted based on students' needs. The 6th grade sessions introduce all students to mindfulness with a six-week workshop. Group leaders implement this curriculum within the context of small groups, which also exposes 6th graders to the small group structure later used for therapy in 7th and 8th grades. Foundational to the student experience at East and potential participation in the later grades, this six-week curriculum begins to build trust and authentic emotional connections that address student vulnerabilities.

Seventh- and eighth-grade students experience the full-year PYR program. The 7th grade program involves small-group sessions, which include students eligible for trauma-informed care based on screening. The program continues teaching mindfulness and adds cognitive behavioral therapy techniques—skills shown to promote resilience in adolescents.

After realizing that students also sought a place where they could process their trauma more directly, we modified the 7th grade curriculum to include an additional component: psychoeducation on trauma—learning about the trauma that children experience and how it affects the mind and the body. We also added in time for students to discuss their own traumas.

In 8th grade, the curriculum continues trauma therapy while homing in on and refining mindfulness and cognitive behavior therapy skills, with an emphasis on generalizing those skills to classroom and other environments.

Mindfulness skills can help students manage distress, lessen impulsive urges, regulate emotions, and identify goals. A typical group therapy session in 7th or 8th grade might open with a mindfulness exercise like the "feelings check-in," where the therapist leads the group in identifying and sharing a feeling each person is experiencing in the given moment. They begin with a simple breathing exercise that helps them focus inward. Then the therapist models sharing by saying aloud: "I am feeling …", and fills in the blank by identifying a feeling or emotion printed on a chart. Students take turns doing the same. (The Stop, Breathe, Think website has a sample emotions chart in its social-emotional learning resources.) Other mindfulness exercises give students time to discuss and honor their experiences. In one session, for example, therapists provided a sealed box where students could privately deposit a written caption of their personal adversities. Everyone agreed that the box would only be opened once full, to protect anonymity. When they opened it, students read each other's brief captions; they paused on each and held space for that person's suffering. "My dad is an abuser," "I was raped when I was seven," "My brother is in prison," "My mom is addicted to drugs." Pauses allowed time to feel empathy and to write validating responses to surround each adversity with acceptance. Students began to feel understood and less alone by reading others' experiences and holding space for each anonymous yet familiar suffering.

Another skill students learn is validation—to observe and acknowledge how another person may be feeling. Students communicate validation and support of another person in group sessions with this step-by-step exercise:

Make eye contact and actively listen.

Be mindful of verbal response.

Be mindful of nonverbal reaction.

Look for the person's emotion (love, joy, surprise, anger, sadness, fear).

Reflect what you are observing, "You seem surprised," "It makes sense why you are irritated," "I would be sad, too."

Remember we are all different and each of us may have different feelings, thoughts, and actions about something.

Remember that validating does not mean that you agree with the way the person thinks or behaves or responds. Validation means that you are present and see how the other person may be feeling.

Respond to others in a caring manner that shows you take them seriously.

Students practice these steps, first by looking at a picture of a person and imagining an interaction. Then they practice with each other.

Lessons Learned

During the three years that we have been providing this program, we've seen progress. At the end of each year, we conduct pre- and post-program resilience screenings, and have found that students who complete 75 percent or more of the group sessions all show improvements in resilience—an encouraging indication that the PYR intervention is effective. Moreover, high-risk students who participated in the 7th and 8th grade group intervention scored similarly in resilience compared to their lower-risk peers by the end of the school year. As one student said: "Instead of getting angry, we use our words."

We've also learned a lot from listening to our students and adjusting the program to their needs. We've created a list of lessons learned from implementing this kind of work that we think is valuable to other schools that might be interested in developing a similar type of program:

Develop trust early. We found that during the screening phase, most students needed more time to develop trust, especially students new to the school. Students were underreporting. However, once they learned in group sessions why the screening questions were asked and who would see their answers, they explained that they would have answered more honestly during the screening, acknowledging their ACEs more candidly. We took this under consideration and have since developed a screening script with supportive language and explanations to help prepare students for the questions.

Create norms for groups. Once students feel safe within their group, understand that many of their peers have gone through similar experiences, and believe in the group's confidentiality, they are not only willing to share, they look forward to it. Students learn how to discuss their adversities openly, often for the first time.

The group therapist is important to this feeling of safety. For our program, therapists were all masters-level clinicians (school social workers, school counselors, or social workers from the university) with training in providing group therapy. The therapist must be open to feedback, willing to accept and validate students' feelings of anger and sadness, and maintain the safety of group space. If these conditions are met, students rarely miss sessions or request to leave.

Foster collaborative relationships. The people our Promoting Youth Resilience students interact with most directly are the university's medical center therapists. The students see them as an integral part of the school community. We believe the measures we took—such as including clinicians in faculty meetings, providing dedicated office and group therapy space in the building, and scheduling regular meetings with school counselors, social workers, and students—ensured this integration. Students see our community partners as staff members, not as separate service providers.

Remember teachers. Teachers at East also experience a great deal of stress and vicarious trauma through their students. They need additional support. We provide interested teachers with a four-session intervention to learn specific stress reduction techniques for themselves that can be implemented within a classroom environment or student interaction.

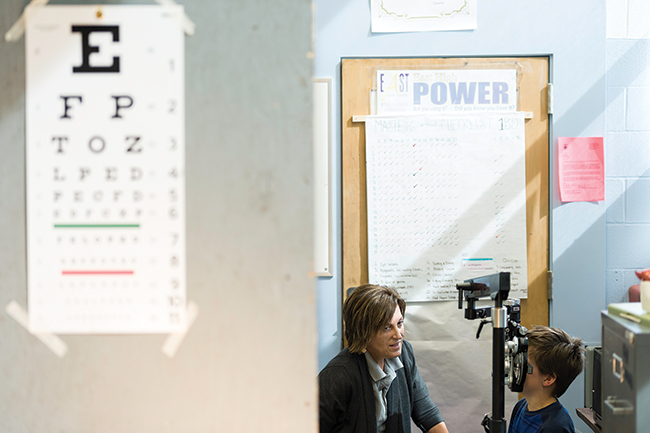

Thanks to a partnership with the University of Rochester School of Nursing, East High School students have access to an onsite health clinic.

Reducing the Stigma of Trauma

We hope to continue to monitor the resiliency our students have acquired as they move through the school system and beyond. We would love this program to be a model for other schools and for East to become a training site where school officials, staff, and community partners can learn the program and take it back to their own schools.

We know that ACEs have a negative impact on educational outcomes. But we also know that it doesn't have to be that way. Resilience-focused interventions can help students deal with past trauma and prepare them going forward. Traditionally, such programs are offered in the community and often come with issues of stigma, accessibility, limited duration, and funding. Delivering effective interventions within the school systems removes these barriers. School-community partnerships can play an instrumental role in creating a trauma-responsive educational system.